In 1909, The Letters of Harry Peyton Steger contain correspondence between Steger and Harold Abrams in Dallas. Apparently Abrams was considering a "journalistic endeavor" and he wanted a little advice from Harry.

"You may look to me for whatever help I may be able to give you," Steger promised.

Evidently Jean Baptiste Adoue, a man that would later be elected mayor of Dallas, had spent several days with Harry the previous week and this project had been discussed at length.

"If you are going to do a book review," Steger instructed Abrams, "for the love of your fellow men veer as far away as you can from the perfunctory and stereotype. I estimate there are three or four different kinds of book reviews: 1. Everybody should read this book. 2. This is a book everybody should read. 3. Nobody should fail to read this book. Some reviewers think they are under an obligation to the publisher in return for an editorial copy of the book to perpetrate something of this sort. This is in great confidence, for the brood would turn and rend me."

Steger suggested substance over frills.

"Let it be as unadorned as a Quaker maiden," Harry advised with typical descriptive flair.

Steger also warned against the primary cause of demise from similar projects.

"They tell me," Harry relayed to Abrams, "that the greatest cause of the failure of the numerous magazines that do fail every year is a lack of a little more capitol."

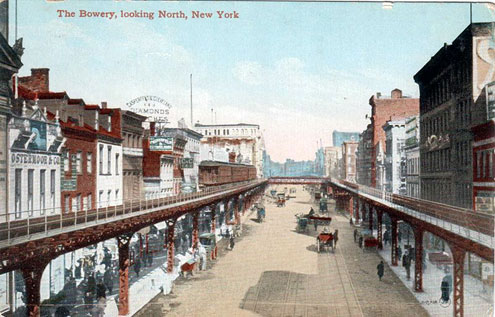

Reoccurring shortages of capitol were also famously plaguing one of Doubleday, Page and Company's most lucrative accounts and one of the country's top short-story authors, William Sydney Porter. Writing under the pseudonym O. Henry, Porter was now raking in about $800 per story and he completed over 600 stories during the eight years he frequented Hell's Kitchen, riverfronts, the Bowery and market places of New York City -- Baghdad on the Subway, as he called the burgeoning metropolis.

Yet, despite Porter's prodigious output, publishers were accustomed to a steady stream of complaints from the writer in regard to his inability to function with an empty purse.

Looking back, maybe the only time trickle-down economics ever truly functioned as promised was when Porter got paid. Every hard-luck story that crossed his path got a hand-out, and Porter's haunts were full of people struggling to survive. Every bartender that could turn out his favorite drink was rewarded for his effort.

A story was told that once Steger showed up at an appointed meeting place up with an advance payment after a plea from Porter. They passed a homeless man on the first corner and Porter tossed the fellow a $20 Double Eagle gold piece. The surprised panhandler even chased after his new benefactor to make sure this overly generous gift wasn't a mistake, but Porter waved him off. When the tide came in for Porter, everyone's boat got a lift.

Put yourself in Harry's place. The phone had rang about 10:00 p.m., and that late hour almost made it a sure bet that either something was wrong back in Fannin County or Porter was in dire straits again.

"Say, uh, Colonel," the voice on the other end of the line began. No doubt Steger would have breathed a sigh of relief that at least this call wouldn't bring bad news from home.

"I'm hard-pressed to come up with $86.14 by nine o'clock tomorrow morning," Porter confided, "and it occurred to me that perhaps you could meet me at 10:45 this evening for a financial infusion and literary counsel."

According to the one and only newspaper reporter ever invited to interview Porter, George MacAdam of the New York Times, this was standard modus operendi, with Porter asking for to-the-penny sums, often ending in 14, that were needed at an exact time. It seemed less like stepping out to help a friend than stepping into a plot. According to MacAdam, Steger had already become Porter's bookkeeper, banker and financial guardian.

On one hand, it is hard not to try and imagine Steger's face, after hurriedly dressing and racing to the aid of his friend and client, only to watch Porter toss a sizeable handout to the first hard-luck case that crossed his path. At the same time, Harry may not have even blinked. Not only was Steger an easy mark in his own right, but he was beginning to package and market the collective work of O. Henry in a way that would reap rewards for Doubleday, Page & Company for decades to come. This was no time to quibble over $20.

Evidently, Doubleday, Page & Company turned the management of William Sydney Porter over to Steger when Harry was only 25. That would seem to be the case, because MacAdam's article appeared in the New York Times on April 4, 1909 and the article came after several weeks of trying to track down the elusive author. Steger had turned 26 on March 2.

The time that Steger and MacAdams spent attempting to corner their prey gave the reporter time to learn more about his subject. Steger told of how Porter had disappeared for a couple of weeks before calling one night for another advance.

"Hey, where in the world are you?" Steger blurted out.

Harry had stopped by Porter's place at the Caledonia several times to no avail. His secret knock had echoed in the silent, empty room.

"Come visit me at the Chelsea," Porter explained.

Steger arrived to find Porter occupying a six-room suite and wearing a blue dressing gown.

"Please excuse the negligee, but my clothes are all being cleaned," Porter offered as Harry plopped down in a chair across from the author's writing desk.

"Help me understand what we are doing here?" Steger asked.

"Well, I owe them so much at the Caledonia that it is weighing heavy on my pen," Porter admitted.

"So, you have given up your place at the Caledonia?" Steger muttered, mostly to himself, as he struggled to apply logic to this surprising development. He heard himself nervously tapping the desk with a finger and slid his hands into his trouser pockets.

"Oh no, I've got those too," Porter shrugged. "I just couldn't write there under the awkward burden of indebtedness. I'm certain this fresh perspective will result in a couple of quick stories, allowing me to square up and move back under more pleasant circumstances."

The irony of this situation is that, a few short years before, Steger had been on the verge of being named a Rhodes Scholar before he had learned the basics of balancing a checking account.

William Sydney Porter was the most unusual of literary figures. In an era when writers captured the public's fancy like no other -- this was still a couple of years before Mary Pickford elevated the role of actors in silent films with her first role in 1912 and the Golden Age of Radio wouldnít begin until the 1920s -- no one could convince Porter to cash in on his growing reputation. He wanted no awards; allowed no photographs; granted no interviews.

All Porter seemed to really need was a chance to create the stories that kept him alive. The people in the street were oxygen to the breathless writer. New York City embraced its devoted scribe as a working-class hero.

Still, even Porter had to acknowledge glaring flaws in this strategy.

Newspapers had decided that Porter's notoriety could be used to help them sell a few extra editions, one way or another. The worst example was when "that infernal paper in Pittsburgh" featured an article that said a delirious O. Henry burst into the office wearing filthy, tattered clothes, his stringy unwashed hair swirling as the disheveled author waved a handful of unsold manuscripts in the faces of employees at work in the room. According to the Pittsburgh article, O. Henry had bummed a dollar from a stunned staff writer before storming out of the room.

It would seem that Porter had actually been in the Pittsburgh newspaper office because, during his official interview with Steger and MacAdams, Porter stated, "Why, I was the best-dressed man in the office, with the possible exception of the editor whose shoes were perhaps a bit more pointed than mine."

About a year passed before someone showed Porter the defamatory newspaper article and the incensed author made a special trip to Pittsburgh. Arriving at the office, Porter handed one of his cards to the secretary. After a minute or two of uncomfortable silence, Porter found himself standing face to face with the unscrupulous "libeler of his solvency."

Staring straight into the man's eyes, with measured breath, Porter exclaimed "Sir, I have come to whip you!"

"But wasn't it a bully good story?" asked the editor with shocked indignation.

The man had unknowingly hit the proverbial nail on the head. In 1894-1895, Porter had published a humorous weekly in Austin, Texas called Rolling Stone that specialized in satirical articles and sketches, both done by Porter, that poked fun at well-known people.

What goes around comes around. Porter had just been poked.

But any reminder of those long lost days when his wife Athol would be waiting at home after Porter put in a dayís work in the General Land Office and their daughter, Margaret, would fall asleep in his arms must have been a soothing respite for the lonely writer. To borrow a phrase from the old short-story master himself, Porterís eyes must have, just for a breathless moment, gleamed the faint protest of cheated youth unconscious of its loss.

The Pittsburgh editor was caught off guard by the sudden change. With tilted head and furrowed brow, he watched Porterís grimace fade to a peaceful smile.

Porter admitted that the article was, indeed, a very interesting read and he bought the editor lunch.

Editor's Note: This section of the Steger series depends heavily upon the one official interview William Sydney Porter allowed. However, the interview produced two separate articles, one by George MacAdam for the New York Times and the other by Harry Peyton Steger that ran later in the Dallas News.

Previous Steger articles:

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110485.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110483.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110478.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110479.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110480.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110481.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110482.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110486.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110487.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110489.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110490.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110491.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110520.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110521.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110522.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110523.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110596.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110597.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110598.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110599.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110600.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110601.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110602.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110606.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110607.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110608.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110609.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110610.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110611.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110612.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110613.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110614.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110984.shtml