Harry Peyton Steger's scout, a term for the servants that looked after Oxford students, found him at four in the morning, delirious and writhing in agony. It was the middle of May 1906, and, perhaps, the beginning of the end.

The servant raced out of the room, only to franticly return, scarce minutes later, with a doctor he had awakened and told of the dire circumstance. The prescription, quite common 100 years ago, was for repeated doses of morphine. The delirium continued for a day or so, leaving Steger weak and trembling.

Over the course of the next week, Harry seemed to slowly recover from the mysterious malady. Then, eight days later, his scout was awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of a thrashing, agonizing Steger.

And this time even morphine couldn't touch the pain.

Harry was admitted to the local hospital, but eventually released in eight days.

"Please don't be alarmed," Harry had written to his parents after first being hospitalized, "for the danger is past. Although the week has been a painful one, it has not been without good results; for my side seems, the doctor says, to have strengthened wonderfully. Perhaps, after all, I shall sail home later, in case I get rid of whatever it is that now offends my flesh."

A scant three days later, however, another onslaught left Steger weak and confused. The Oxford staff was bewildered.

"Tomorrow I am being sent to London for an expert to 'tap' and 'thump' me," Steger informed his distraught parents across the Atlantic. "Please do not think this is a blue letter. I have decided to tell you exactly the state of my health."

"The whole plaguly business was beginning to get on my nerves," Harry admitted later in a letter to his uncle, Ed Steger. "Friends of mine in college and some of the college authorities told the famous Olser of me. He came to see me; sent me to London under nurses' charge to be X-rayed. Nothing showed. On my return, he analyzed my urine, found uric acid in large quantities, hinted strongly at Bright's disease, gave me alarming advice about my future, sent me to Karlsbad."

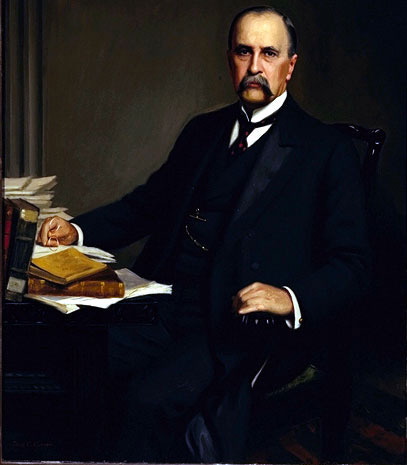

The physician Steger refers to as the "famous Olser" was none other than Dr. William Olser or, later, Sir William Olser. Olser became the first chief of staff at Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1889. Harry had met Olser in 1904 at Johns Hopkins University, more than a decade after the legendary physician and scholar became one of the first professors of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893. In 1905, Osler was appointed Regius Chair of Medicine at Oxford and, about one year later, he was passing along a rather gloomy prognosis to the Rhodes Scholar from Fannin County.

And one can only guess about the bedside conversations between Olser and Steger, because Olser was much more than an icon of modern medicine and a gifted author who also collected a staggering array of historical medical data. Olser was a magnificent joker who, in 1884, submitted what we would now call an urban legend in the form of a pseudoscientific submission called penis captivus that sailed straight over the heads of the knowledgeable editors of the Philadelphia Medical News.

It is humorous to note that a young Harry Peyton Steger once gleaned much satisfaction from sending false accounts of seemingly prestigious gatherings to the editors at Dallas News and then chuckled upon their publication.

Sir William Olser is probably best known, however, for insisting that doctorial students would benefit immensely from visiting, studying and conversing with patients, a concept that developed into the medical residency program. Olser understood the accelerated learning that would take place once medical students were taken out of the lecture hall and, instead, allowed to perform lab tests and actually placed at bedsides.

Harry was in good hands.

Still, during this timeframe, Bright's disease--chronic inflammation of blood vessels in the kidney--was a rather general classification for several different forms of kidney disease.

Dr. Olser recommended Steger seek treatment in one of the therapeutic spas that dotted Karlsbad's famous hot springs and Alexander Cowie, an Englishman of independent means, arrived with Harry at the Angers Hotel in Karlsbad, Austria early in June of 1906.

"This is a beautiful little place, situated deep in a lovely valley," Harry relayed to his anxious parents in Bonham, "and, were it not for plutocrats (a class in Europe composed of Russian princes, English aldermen and American brewers), no more delightful spot could be imagined. Their presence, however, makes expenses soar aloft and gives more of the purse-proud air to the place. I am quite confident this system of waters will rejuvenate my kidneys..."

Harry had known something was "offending the flesh" in April of 1906 when, following an afternoon of vigorous exercise, he felt a stabbing pain in his right side. Three months later, after a rapid succession of excruciatingly painful attacks, Dr. Olser had hinted of a future clouded by diabetes and Bright's disease. But two weeks in Karlsbad under the care of a "dear old grandfatherly chap," Dr. London, worked wonders.

"I am happily rid of my stone!" Steger wrote to his parents on June 13, 1906. "Think of that! Of diabetes and Bright's disease, which Olser had intimated as being possible developments, Dr. London declares there is no trace. Regular hours, good diet and these cleansing waters will leave me in far better condition than I was. Dr. London says I came in the nick of time. Four more weeks will see the end of my Karlsbad treatment. I will gladly come home then, if you and mither say so."

Harry's English friend, Cowie, remained in Austria for a month with Steger before taking the long way home to London. It seems Cowie's inability to speak the language contributed mightily to the fact that he found himself on a train wandering through Holland before someone finally directed him to England.

Meanwhile, Steger had become fast friends with Richard Conried, son of an important New York City theatre director. Dr. Holland insisted on two weeks of a vigorous lifestyle following the treatment, so Steger and Conried set off on a motorized mountain tour of Western Central Europe.

"Conried is taking me for an eight-day's trip in Tyrol in his father's big motor car," Harry tells Ed Steger. “After that, I am visiting a Dutch friend of mine in Holland for a few days, then a short visit in Germany and then to Bremen for the boat to America. I wish my father and mother could realize how small the world is, after all. It is shrinking, too. The fast boats and cables are doing it. At present, cables and letters to consuls have rendered me an object of suspicion to the Austrian police. Please re-assure my people."

Previous Steger articles:

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110485.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110483.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110478.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110479.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110480.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110481.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110482.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110486.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110487.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110489.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110490.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110491.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110520.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110521.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_110522.shtml