The year was 1909.

Geronimo would die February 17 at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

O. Henry was hurtling towards the same destiny as the troubled writer continued to drink himself into an early grave.

John Lomax had completed his master's at Harvard and returned to College Station where he was teaching English at Texas A&M and putting together an anthology, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads.

Evidently, Harry Peyton Steger's duties at Doubleday, Page & Company that year included playing tennis in the mornings with Booth Tarkington and then escorting Mrs. Tarkington for sunny afternoon drives.

Roy Bedichek was soaking up a little sunshine himself. Bedichek was on a bicycle, riding out of a small town near Waco and bound for El Paso, 800 miles away.

That distance, though considerable to say the least, doesn't reveal the challenges he faced. One hundred years ago, there wasn't even a road to follow much of the way. But there was a trail that ran along side the railroad tracks that Bedichek knew would eventually lead him into El Paso.

At first, torrential rains turned the primitive country roads into a muddy mess, forcing Bedichek to retreat to a hotel in Bartlett for almost a week. Then, after San Antonio, it was sand, not mud that slowed the bicycle trek.

Much of the time, Bedichek spent pushing his bike along the tracks. A chance meeting with a farmer might lead to a welcome trade for both participants -- a day or two of work for a few precious square meals. A deep hole in a creek might lead to a day or two of fishing.

Steger had waxed poetic in letters to his dear friend "Bedi" about daring to escape to a place where there was no money and no need for money. At times an intoxicating siren song from Tristan da Cunha, the most remote volcanic archipelago in the world, seemed to lure both men to the tiny, isolated South Atlantic islands midway between the tip of South Africa and South America.

All the while, there was a very sparsely populated territory just to the west of Texas, a mystical desert land of cactus and mountains that would become home to writer D.H. Lawrence and artist Georgia O'Keefe in the 1920s. Bedichek had set out for the New Mexico Territory over a decade before either Lawrence or O'Keefe set their sights on the Land of Enchantment and surely neither the writer or the artist had a journey that could compare.

Bedichek had to survive by his wits as he traversed the vast and barren West Texas landscape -- his bicycle odometer had registered 965 miles when the odyssey was over.

It was exhilarating to leave behind the constraints of civilization and, along with it, the dread of being caged for life.

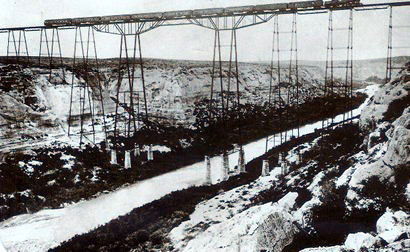

And Bedichek's heart raced as he eased his bicycle out onto the framework of the highest railroad bridge in America and looked down at the Pecos River hundreds of feet below.

Built in 1892 by the Phoenix Bridge Company of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, the rails of the high bridge were 321 feet above the Pecos River, making it the third highest railroad bridge in the world at the time. The 401-foot Garabit Viaduct in France was built in 1884 and the 336-foot Loa Viaduct in Bolivia was constructed in 1889.

It was more than a third of a mile across the metal viaduct structure. Bedichek had heard that trains would slow as they approached the bridge and then ease across, giving passengers time to appreciate the spectacular vista of the gorge and river far below.

Starting across the expanse, step by measured step, Bedichek could see the terrain fall away with dizzying clarity through the gaps between the crossties until finally the Pecos River came into view over 320 feet below. He paused to take in the remarkable sight, steadying himself against his bicycle as a north wind whistled through the canyon and pushed at his back.

Bedichek glanced over his left shoulder; everything he knew -- his family, the woman he wanted to marry, every friend he'd ever known --everything and everyone was that direction. But he turned the other direction.

They were giving away land out west.

At long last, Bedichek pedaled into El Paso, sold his bicycle to the barber that was giving him a shave and grabbed a ride on a freight train bound for Deming, 100 miles to the west in the New Mexico Territory.

The best way to describe Deming in 1909 was that there were 3,000 residents and 16 saloons. Cowboys came riding up Main Street, leaving a trail of dust all the way to their favorite watering hole. And, of course, any territory filled with cowboys, lonesome homesteaders, land agents and well diggers will also have a contingency of ladies in pink tights that catered to the cowboys, lonesome homesteaders, land agents and well diggers. Supply and demand of the original sort.

But people in Deming, for the most part, minded their own business and displayed a level of civility and respect toward each other. To Bedichek, this was the last frontier and these were the last free people in North America.

He filed a homestead claim on 320 acres of desert land about nine miles south of town, nestled at the feet of the Florida Mountains. A few odd jobs as a stenographer allowed Bedichek to hire a fellow to help dig a well and build a 12x14-foot shack on the claim. Now he could be alone on his island, albeit one of the desert variety, to write to his heart's content.

Bedichek wrote and submitted newspaper articles, along with technical writing about irrigation and farming in the arid southwest. At night he lay in the tent he had stretched next to his shack and wrote poetry to Lillian Greer in Waco, where the Greer family had just built a fine new home, with indoor plumbing, no less.

In The Roy Bedichek Family Letters, it seems Bedichek was very honest about the harsh realities of life in the New Mexico Territory. The newspapers articles were, at best, a very limited success.

"I live on frijole beans and rabbits which I catch in traps," Roy wrote to Lillian. "I live like a lone wolf in a canyon. There are cracks in my shack you can throw a cat through and my tent is getting a little ragged."

While his stab at being a correspondent missed, the poetry found its mark. In 1910, Lillian kissed her mother goodbye and climbed on the train. Two days and 900 miles later, Lillian saw Roy waiting on the platform when the Golden State Limited rolled into Deming.

If up the sky in burning flight

Some mad star scorched its way

And if the mark, blood-red by night

Turned black as night by day

My love I'd liken to that star

Which did so wildly start

The mark I'd liken to a scar

Which burns across my heart.

-- Roy Bedichek