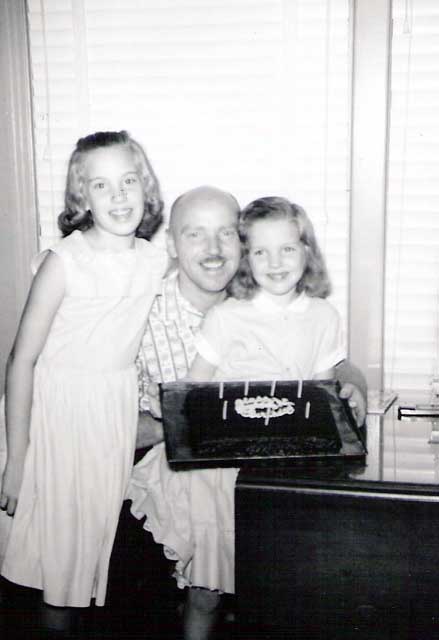

Saying Good-bye to Daddy

Next month marks three years in which I have dealt with my

father's decline into dementia. What started slowly with mere confusion has now become a gallop into another world. Sometimes, it's the past. Most times, it's a combination of the fantastic and the small hold he has on his ever changing version of reality.

Three years ago, his second wife was dying of cancer. He was

understandably stressed, his eighty-year-old mind trying to hang on to

both his business and the care of his wife. Hospice allowed him to

relinquish some of the physical demands and I thought, in my naiveté,

that when she died, the pressure would be off Daddy and he would resume his daily responsible life.

But it didn't happen. He became worse, not paying attention during the days I was not there, to the notes I would leave in his checkbook

("Don't send money to any magazines!"). By the time I had the problem partially under control, he had over 50 subscriptions to periodicals, several of them multiples of the same thing. He was bombarded with 're-subscribe', 'lock in your low rate', and pitches from third-party magazine vendors. He couldn't discern the difference, so he answered--and sent money to--them all.

As he did for other mail. I have no kind words for sweepstakes and

psychics, can spare none for spurious charities that prey on the

elderly. Don't get me started on politicians and political campaigns

that pounce on the insecurities of the very population they have

pledged to protect.

Had I not been a cynic before, I would have become one.

My sister and I agreed that Daddy needed to move closer to

me, to give up his own house, to retire from the business he had built.

He wasn't thrilled, but he did it. We gave him no choice. A

strong-willed father couldn't compete with the two strong-willed

daughters he had helped forge.

From visit to visit in the assisted living facility, he would

question me about his affairs, then forget what I'd told him the day

before. Then forget from the hour before. Five minutes. What we had

just discussed.

Over two and a half years, his decline became so pronounced

that he now lives in the Alzheimer's unit at the Clyde W. Cosper Texas

State Veteran's Home. I do not pull into the driveway without thanking

the powers-that-be that not only does this facility exist, but that it

does so close to me.

He has been there less than a month and already he has

changed. The slippery slope of his rational being has become a cliff

and he is poised on its precipice. He knows who I am (I hear the day

will come when he will not) and variously knows my husband and that I

have a sister. The photos of his grandchildren are the photos of

strangers. He knows that where he is he doesn't want to be, but it's

been a week since he's followed me to the door and begged me to take him with me. It was easier to leave my infants with daycare strangers than my father on the other side of a locked door.

Our conversations are round-robins of 'when can you get me

out of here' and 'who's running the farm?' He shook the hay of his

family's dairy farm from his boots when he was 17 and he never looked back. At least not until his mind collapsed the sixty years between World War II and now into yesterday. Yet some ideas remain fixated in his mind: that he has a business and that he needs to be running it.

But he can't remember Mother, his wife of over 50 years, unless

prompted. I don't mention his second wife.

I will not dwell on the man he used to be. The Daddy I knew as a child

is just about gone from behind his eyes. He looks at me blankly. I have

had to come to terms with the fact that he's not coming back. I've had

to say good-bye to the first most-important man in my life, and I've

had to do it while he is still alive.