|

| Red River |

Front Page

Land of the bois d' arc, Fannin County share fascinating frontier history

By Allen Rich

Aug 22, 2005

The next great TV epic could very well be called "Bois d’ Arc." No, film crews aren’t feverishly trying to find Bonham on a map as you read this, but the history of this native tree could keep Lonesome Dove author Larry McMurtry busy for years. Indians fought over thick groves of bois d’ arc trees where they harvested the heartwood for their prized bows.

A bow fashioned from this remarkable wood was said to be able to propel an arrow through a buffalo…or a foe. Come bartering time, a finely balanced bow was worth a good horse or a comely, young squaw. That’s more material than most feature films have to work with these days and we haven’t even knocked the bark off the story of the bois d’ arc tree.

Red River

A yellow dye was made from the roots and inner bark. One fascinating part of this story is that early historical documentation suggests when the very first bois d’ arc tree dropped the first horse apple, it hit the ground in Fannin County.

The first documentation of the remarkable bois d’ arc (Maclura pomifera) tree came from a report to President Thomas Jefferson by John Sibley and Merriwether Lewis just over 200 years ago in 1804, but they were only relating information they had gathered from transplanted saplings. For a short period Sibley was an Indian Agent and he was aware of a lively trade of these prized bois d’ arc bows coming from tributaries along Red River.

Probably the first actual documentation of bois d’ arc trees came from the Dunbar and Hunter Expedition up the Ouachita River in 1804 and 1805, but knowledge derived from native guides explained that even these specimens had been transplanted from a great distance. When questioned about why someone had made that effort, the guides told about the unique elasticity of this “yellow wood” that also made a potent dye. French trappers and traders had already brought back examples of this dye to Europe. The word was out about bois d’ arc.

Hunter wrote back: “Perhaps this is the famous tree which yields the yellow dye [held] in so much esteem in Europe and reckoned so valuable and rare, capable of dying the finest scarlet.”

But where was the mother lode, the source of these transplants?

Peter Custis found the answer.

The original scientific description of the bois d’ arc tree came a little over 200 years ago, in 1806, when Custis studied a transplant about eight feet in circumference that had grown to 30 feet in height near Natchitoches, Louisiana. The men just happened to have some whiskey in their possession for scientific purposes, so Custis preserved the fruit, commonly called a horse apple in North Texas, in a jar of whiskey and sent the specimen back to President Jefferson.

Jefferson had sent Custis, a naturalist, and surveyor Thomas Freeman to ascend Red River to study the newly purchased Louisiana Territory. William Dunbar, a scientist from Natchez Mississippi who wrote Jefferson in 1804, was urging the President to action. Dunbar told of a river that “run a very long course thro’ immense regions of the richest and most fertile lands.” Dunbar had walked away from an earldom in Scotland to explore the New World in 1771. He was a brilliant man of vision and far ahead of his time. Jefferson shared those qualities and the President’s interest piqued. Dunbar said this area “will hereafter support a prodigious population.”

Much of the excitement was fueled by stories of a river that would lead all the way to Santa Fe and the Rockies. Back in 1739, French traders Paul and Pierre Mallet had visited Santa Fe and then told of returning to civilization on a river with a red hue. It wasn’t until 1820 that Stephen Long found that the red-colored river running east from the foothills of the Rockies was the Canadian River. Jefferson didn’t have that information and all indications back in 1804 were that this legendary red river would provide the most direct route to the most northern Spanish cities. The President received some of Dunbar’s reports in 1804, less than a month after Lewis and Clark headed west in search of the Northwest Passage.

Jefferson dispatched Custis and Freeman.

In the spring of 1806 a mini-frontier armada of rafts and canoes began the journey up Red River, however a Spanish army unit convinced the expedition to turn back near what is now the Oklahoma border. The second attempt was successful, allowing Custis to document the natural resources along Red River. He felt the first native stands of this interesting tree that produced the large green inedible fruit occurred just above the Kiamichi River in Southeastern Oklahoma. Custis believed the major source of this unusual tree was centered on a tributary to Red River many miles upstream that was a favorite of French beaver trappers. These early North Texas visitors already realized that Caddo and Osage Indians harvested the wood for their prized bows here. The French were compelled to name this creek bois d’arc, meaning “wood of the bow.” So even the name seems to provide some collaboration the muddy creek that runs just east of the Bonham city limits was the place that the bois d’ arc tree originated.

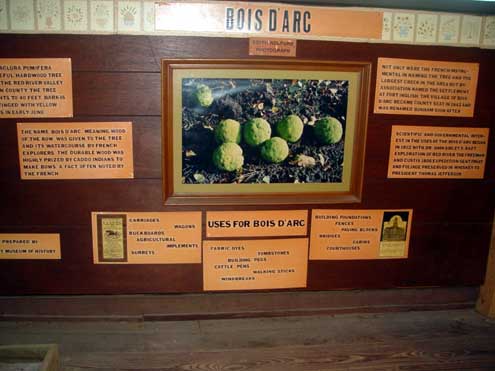

Tom Scott, the director at the Fannin County Museum of History, has a much cuter story about plant “A” winking at plant “B” and the impending cross-pollination somehow gave the world a fruit that only a squirrel can enjoy. Or maybe that was just my version of Mr. Scott’s story, but the museum has a very informative bois d’ arc display, including an actual bow made of the legendary wood. Obviously, the true “fruit” of this species is the wood that was once considered the most elastic wood in the world and the “fruit” was also the yellow paper-like lining of the roots and inner bark that produced a treasured dye. Modern day North Texans mostly consider bois d’ arc a fencerow nuisance, but in it’s day this tree grew roots into Europe. In a small way it still does. Woodworkers the world over have heard of the qualities of this yellow wood and there is still some trade, mostly over the internet these days, of straight “blanks” so a traditional bow can be fashioned from the favorite wood of Native Americans.

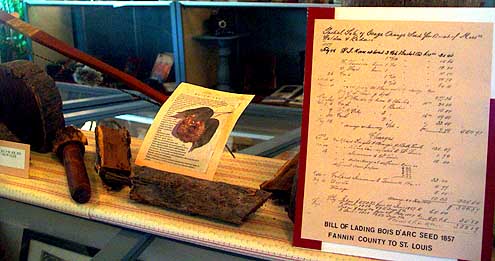

From the 1850s through the 1880s, the settlers in many ways harvested this tree. Bois d’ arc brought jobs to Fannin County. The wood makes great fence posts and even the Fannin County Courthouse sits on 15-foot long bois ‘d arc poles sunk into the ground. Circular “rounds” were shipped to Dallas to pave streets. Spikes made of bois d’ arc were hammered into holes in order to connect beams and rafters in buildings at one time. The Fannin County Museum exhibit has examples of these spikes and rounds. They even have a horse apple, in case you “ain’t from these parts.” Primarily, it was the seeds that people wanted and there was a brisk trade to the Midwest and lower plains where bois d’ arc was used as a wind block and also for a type of fencing. The seeds were planted in a concentrated fashion and that produced an impenetrable hedge. With the introduction of mass-produced barbed wire, the bois d’ arc seed business no longer bloomed. Only a few craftsmen worked with the wood after the turn of the 20th century, although Mr. Scott remembers the John and Dorothy Loftin home north of Bonham in the 1940s having a beautiful room with a fireplace and a floor made of yellow bois d’ arc rounds.

Another interesting fact is that it turns out we are on the verge of what could be called “The Bois d’ Arc Bicentennial” because the 200th anniversary of the expedition President Thomas Jefferson sent up Red River is only a few months away.

Sounds like a party to me.

Exhibit at Fannin County Museum of History

Exhibit at Fannin County Museum of History

Exhibit at Fort Inglish Village

Many homes in this area rest on bois d' arc blocks like this one from the birthplace of Charlie Christian. When bois d' arc is alive, it cuts and splits relatively easily. Once bois d' arc ages, it becomes so hard a chainsaw blade can throw sparks when it hits the dense wood.

Exhibit at Fannin County Museum of History

Exhibit at Fannin County Museum of History

EDITOR”S NOTE: Please allow me to admit that almost everything I know on this subject comes from a very interesting book, Jefferson & Southwest Exploration, The Freeman & Custis Accounts of the Red River Expedition of 1806 written by Dan L. Flores. Mr. Flores won the 17th Annual Coral Horton Tullis Award for the most important book on Texas with this fascinating chronicle of a trip up Red River when this was uncharted territory.

It might not be much of a stretch to think of Jefferson’s attitude as “Texan” when it came time to draw up boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase this visionary President felt could be arguably defended. If you must exaggerate, at least be good at it. Jefferson was very good at this art, and whether you believe he was an uncommon man with a vision for how future generations would best be served or whether you feel many decisions were simply unbridled imperialism, Mr. Flores is very good at capturing the times and men of an era that shaped our nation. Jefferson & Southwest Exploration is a very good read for history buffs.

SMU anthropology professor David H. Jurney also wrote a very informative paper, The Original Distribution of Bois D” Arc, that served as background information.

Of course, I made a couple of trips to the Fannin County Museum of History, one of the finest small-town museums anywhere. There are some things we will have to do differently if we ever want Bonham to ever have the look and feel of a tourist hotspot like Gruene, Texas. But this museum is one example of things we have done right. Visit the museum to learn more about the historical importance of bois d’ arc and you will probably find the Erwin E. Smith Western photography exhibit interesting, as well. Mr. Scott and Mrs. Dodson are wonderful hosts with a vast knowledge of North Texas history.

In closing, one man will always come to mind when I think of Red River. I’m not sure anyone ever felt more strongly that Red River never got its rightful place in American history than Fannin County native "Wildwood" Dean Price. Wildwood’s journey down Red River all the way to Louisiana back in 2002 made for great reading the first year North Texas e-News was in the business of finding the best stories from our own backyard. Wildwood’s modern day expedition, with side trips up the Kiamichi River and a big creek in Lamar County, was part Freeman Custis Expedition and part Woody Guthrie, too, when heavy rains sent soaked river travelers scurrying up slippery banks in search of a dry barn to sleep through a thunderstorm while rain pounded the tin roof. Wildwood’s story didn’t have railroad bulls, but he made up for it with alligators. Plus, neither Guthrie nor Custis had a good digital camera, as I recall. If Wildwood doesn’t mind, the 200th anniversary of the Freeman Custis Expedition might be the perfect time to run Mr. Price’s Seeing Red series again.