At 11 a.m. on November 11, 1918, the guns on the Western Front in France and Belgium fell quiet, and the Great War—it would not be known as World War I until another conflagration shattered the armistice twenty-one years later—came to an end. A year later, on the first anniversary of that day, people in Britain were asked to stop for two minutes of silence in remembrance of those who died in the war. What followed was indeed remarkable. The Manchester Guardian recorded this account of the moment in London.

The first stroke of eleven produced a magical effect. The tramcars glided into stillness, motors ceased to cough and fume, and stopped dead, and the mighty-limbed dray horses hunched back upon their loads and stopped also, seeming to do it on their own volition.

Someone took off his hat, and with a nervous hesitancy the rest of the men bowed their heads also. Here and there an old soldier could be detected slipping unconsciously into the posture of “attention.” An elderly woman, not far away, wiped her eyes, and the man beside here looked white and stern. Everyone stood very still…. The hush deepened. It had spread over the whole city and become so pronounced as to impress one with a sense of audibility. It was a silence, which was almost pain…. And the spirit of memory brooded over it all.

Thus was the first “Remembrance Day,” the name it still goes by in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth countries whose soldiers fought in the war.

In the United States, the idea did not gain national recognition until 1926, when a concurrent resolution of congress made November 11 a national holiday designated “Armistice Day.” Twenty-seven states had already set aside the day for observance before resolution.

In 1954, at the urging of the newer veterans of World War II and Korea, the name was changed to Veterans Day. The Uniform Holidays Bill of 1968, which floated several national holidays to Mondays, to create three day weekends, resulted in the first Veterans Day under the new law falling on October 25 in 1971. This was very unpopular, and the permanent November 11 date was restored in 1978.

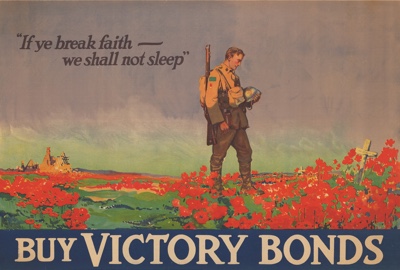

The association of the poppy with the Great War and remembrance reaches into the war itself. In a quiet moment during the second battle of Ypres in 1915, a Canadian doctor running a front line aid station, pulled a page from a dispatch book and wrote a poem.

In Flanders fields the poppies grow

Between the cross, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe;

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Colonel John McCrae sent his poem, anonymously, to the magazine Punch, which published it under the title “In Flanders Fields.” The author's original poem was as show above. When the poem was first printed, "grow" at the end of the first line, was changed to "blow." No one knows why. Dr. McCrae died of pneumonia while on active service in May 1918.

To an American, Monia Belle Michael, goes the first recorded incidence, in 1920, of wearing a poppy in remembrance of those lost in the war. Madame E. Guerin, a French woman visiting America, heard of the idea and on her return to France, began making paper poppies in her home, selling them to raise money for children orphaned by the war. The custom soon spread around the world.

Before she first wore the poppy, Michael had already added a page to the story with a poem in reply to “In Flanders Fields.” She called it “We Shall Keep the Faith.”

Oh!, You who sleep in Flanders’ fields,

Sleep sweet—to rise anew,

We caught the torch you threw,

And holding high we kept

The faith with those who died.

We cherish too, the poppy red

That grows on fields where valor led.

It seems to signal to the skies

That blood of heroes never dies,

But lends a lustre to the red

Of the flower that blooms above the dead

In Flanders fields.

And now the torch and poppy red

Wear in honour of our dead.

Fear not that ye have died for naught

We’ve learned the lessons that ye taught

In Flanders’ Fields.