The train crews called it the “mortgage lifter,” because the 12-hour night, six nights a week trip from Bonham to Sherman and Whitesboro and back made for a hefty paycheck every two weeks. The official name was the West Local.

This distinguished it from the East Local, which ran two trains daily, one east, one west, between Bonham and Texarkana. Even when the East Local left Texarkana heading west to Bonham it was still called the East Local. Geographic exactitude was never a hallmark of the railroad business, grandiosity being more important in the bigger scheme of things. It was this thinking that produced the famed Denison, Bonham & New Orleans, which ran 24 miles from Bonham Junction to Bonham and hence to oblivion, once thought to be a terminus in Marshall County.

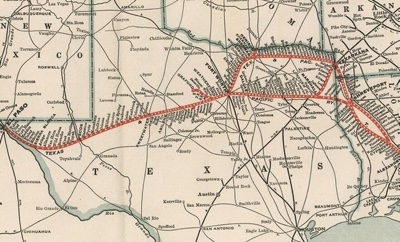

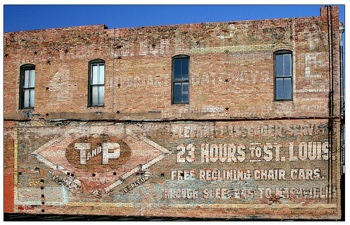

Back in Bonham, Monday through Saturday, the crew arrived at the depot around five each evening to switch and spot the freight cars that had been brought in from Texarkana that same afternoon and were designated for local businesses. Rarely were there a dozen or more cars strung out behind the blue Texas & Pacific or, later on, Missouri & Pacific, diesel heading toward sundown when the local left for Sherman.

It took about an hour to chug the 25 miles to the outskirts of the Sherman yard, where the first order of business was to stop, uncouple the engine from the train and turn it around on the “Y” so that the head end of the engine now faced back toward the east. In the beginning, this was a maneuver that confused me no end.

During the daylight hours, the signals used by the train crews to direct the movement of the engine were pretty straightforward. Swinging your arm in a counterclockwise circle while facing the engine meant come toward me. Circling the other way meant go away from me. It was “come and go,” about as basic as body language gets. A native from the wilds of Borneo could doubtless have figured in out.

Make the circle smaller and the engineer would slow down as the cars being switched neared each other. The circle got smaller and smaller and the engine went slower and slower until two hands, moving back and forth meant the coupling was imminent. A skilled engineer, with good signals from the brakeman could guide the train to a joining of the couplers with gentle, satisfying “clunk,” as the knuckles met and the pin dropped into place locking the cars together. Come together too fast and there was a clang and a bang and things shook and cars jolted and various parties involved swore oaths under their breath.

When the joint was made, the brakeman, brought both hands together in front of his chest and down to the waist, indicating he was stepping in between the cars to connect the airbrake hoses and open the valve that let the engineer control the brakes on the entire train from his seat in the cab. Between the cars is a dangerous place to be and it was important that the engine crew knew where the brakeman was so they would not start the train moving. The whole process took less time to do than to explain, and then it was back to moving and switching and pushing and pulling freight cars around and putting them where they supposed to be.

All this was in the daytime; at night it was back to square one. In the dark, the brakemen communicated with an electric lantern and the simple “come to me—go away from me” was lost to history and replaced by “go forward” or “back up.” These commands were relative, depending on which way the head end of the engine was facing at the time.

Swinging the lantern in a circle was the sign for move forward, waving the light straight up and down meant back up. Moving the light in lower half of an arc meant stop and the twist of the wrist in the upper half of the arc signaled that the brakeman was going between the cars. To make this work, the brakeman had to remember which way the engine, which he couldn’t see in the dark, was facing. After we turned the engine in the Y, it would take me a few minutes to readjust my directions, and until them I was backing up when I wanted to go forward.

Over time, on every road, trainmen had developed other signals, some simple, others complex, to communicate with their fellows who were out of earshot. Two thumbs up followed by a motion like shoveling food into your mouth, meant, “spot the train (park it) and let’s go eat.” There was a sign for “track #1,” “track #2,” and in the Paris yard, the chicken track. This was a siding that led to defunct poultry processing plant. It wasn’t used much, but it was always a treat to watch a grown man put both hands into his arm pits and flap his arm like a chicken to signal his destination.

The caboose, the lanterns, the flapping arms to signal the chicken track have gone the way of much of the traffic along the railroad, on a one way ride into memory. They’ve been replaced with electronic “end of train” markers and men with two way radios who communicate directly with each other and the engineer.

Meanwhile, back on the West Local, after the engine was turned on the Y, the train proceeded to the Frisco interlocker, where a manned signal tower controlled passage through the intersection of the Frisco and the T&P. Railroads always have taken a dim view of trains running into to one another at crossings, or anywhere else for that matter, and so all traffic stopped at the tower until given the OK to go a head.

The interlocker tower, painted a fading yellow and brown, was up by East Street and stood guard from 1903 until 2001. When the road’s new operator, the Burlington Northern, replaced the man in the Sherman tower with a man at a computer in Omaha or somewhere, the building was dismantled and hauled off to Grapevine to become part of that community’s railroad museum. No one in Sherman wanted to save it, so another piece of history disappeared.

A few blocks from the interlocker was the T&P freight depot on North Travis; it’s still there, albeit with a different logo. After picking up a list of work to be done that night in Sherman, the crew would head back into the dark to shuffle freight cars around until dawn, when it was time to go back to Bonham.

After a few trips, one became familiar with the signature spots in the Sherman yard. Quaker Oats was not on the T&P, but the sweet smell of roasting oats (or something, I was never sure what) that filled the air as the train came west from the Y marked one’s arrival in Sherman. Mrs. Tucker’s, by then owned by Anderson Clayton, where they made Blue Bonnet margarine was still Mrs. Tucker’s to the train crews. It was not a favorite spot of mine. The plant, which transformed cottonseed oil, and who knows what else into oleo margarine, put out a thick, cloying, smell, a mix between something already gone rancid and something quickly on its way to going rancid that was hard to stomach.

West of town, out toward Southmayd was an outfit called Line Materials. They took cardboard and tar and made pipe. It smelled bad too, but was not in the same league with the big stink at Mrs. Tucker’s. In fact, the only thing close was a wire plant, somewhere in the Sherman yard that put out a chemical aroma that was less than sweet.

Every night, the big boomer freight trains, 140 cars long, that had started in Kansas City bound for Fort Worth, and had passed their kin going the other way, stopped at a siding near Whitesboro to set out cars destined for places along the T&P. When the work was finished in Sherman, the West Local would head out to Whitesboro hill to pick up the consist and shuffle it into the mix.

If the night’s work had been light and the KO&G (Kansas Oklahoma & Gulf—still called that though the road no longer existed independently) was running late, the local would go on the spot on the siding and wait. Whitesboro hill was the coolest spot on the planet. It didn’t matter if the temperature back in Sherman was still in the 90s; on Whitesboro hill it always was as cool as a November afternoon. Stretched out on a bunk in the caboose, it was a treat to catch a few minutes of sleep, rocked by the gentle rumbling of the engine as it idled in the dark up ahead.

Back in Sherman, the local would deal with the cars brought in from Whitesboro, make up the cars going east and get ready to call it a night. If the job were nearing the 12-hour time line, the crew would insist on their negotiated right to have another meal before they left and troop up to the early opening Grayson Hotel coffee shop or the Travis Street Lunchroom for breakfast. It was more a matter of hard earned union rights than hunger, and all good members of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen (I think that was right, I’ve still got my lapel pin in a box somewhere.) stood by the adage that if “you didn’t use it, you’d lose it.”

I’ve asked some of my fellow trainmen from those times, where we had the mid shift meal when working the West Local. No one remembers, although the consensus seems to be that most of the time we must have brought a lunch from home. Finding a place that was open and serving food at midnight within walking distance of the depot was no easier then than now. Somethings never seem to change.

Finally heading east toward home and the break of day, the train would chug along to Bonham where the East Local crew would climb on board, give the highball and continue on to Honey Grove, Paris, Clarksville, Red River Depot, New Boston, and Texarkana, and the West Local crew would head for home and bed and another trip 12 hours later.