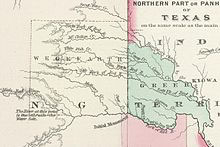

Long before it becomes a river, the Red rises along four tributaries, the Prairie Dog Town Fork, the Elm Creek Fork, the Salt Fork, and the North Fork, high on the Llano Estacado of the Texas panhandle. The Prairie Dog Town Fork begins where the waters of Palo Duro Creek, which start their long journey to the sea in Curry County, New Mexico, join with Tierra Blanca Creek in Randall County.

The fork has wandered 160 miles out of the Llano for 90 million years, cutting deep into the Cap Rock to gouge out Palo Duro Canyon. The canyon, abundant in wood—palo duro means “hardwood” in Spanish—and water, was a haven for prehistoric men, hunters of the giant bison and mammoths that roamed the land between 10,000 and 5,000 B.C.

Twelve miles northeast of Vernon in Wilbarger County, not far from Doan’s Crossing, the North Fork joins the Prairie Dog Town Fork and the watercourse becomes the Red River.

Early explorers thought the North Fork was the Red’s principle tributary. The Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, between the United States and Spain, recognized the North Fork as the boundary between New Spain and the territories acquired by the United States from France in the Louisiana Purchase.

The river was called Rio Rojo by the Spanish, from the red dirt borne along with the flood, and at later times the Red River of Natchitoches and the Red River of Cadodacho. Six hundred and forty miles of its 1,360-mile length are either in Texas or form her border, and along that route the Red draws strength from smaller rivers, the Pease, the Wichita, the Sulphur, the Washita and numerous creeks and streams.

The river flows into Arkansas at the eastern edge of Texas, and then bends south into Louisiana. It reaches the Mississippi 45 miles above Baton Rouge, 341 miles from the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1542, when Luis De Moscoso Alvarado and the survivors of the Hernado de Soto exploration came upon the eastern part of the river, it was home to Amerindian tribes of the Caddo Confederacy, principally the Natchitoches, the Hasinai, and the Kadohadacho. The name “Texas” derives from the Hasinai term táysha for “friend.” Farther west, the Wichita and Tonkawa held sway, and farther west still, on the Southern Plains, the Lipan Apache dominated until they were uprooted and displaced by the invading Comanche.

The French followed, using the river to establish trade with the Caddo and other tribes. By the middle of the 18th Century the Fleur de Lis of Bourbon France flew over Wichita villages near Spanish Fort in Montague County. In 1759, the Spanish, reacted to French incursions and the destruction of the mission at Santa Cruz de San Sabá by northern Indian tribes, by sending a military expedition north under Colonel Diego Ortiz Parrilla to exact retribution.

Ortiz Parrilla had 576 in his party when he set forth from San Antonio de Béxar in the early fall. His mission was to reign in the Tawakonis, Tonkawa, and Wichita. On October 1, the Spanish struck a Tonkawa camp on the Brazos River, killing 55 and capturing 149 along with 100 of the horses stolen from San Sabá. Emboldened, Ortiz Parrilla sent scouts ahead to the Red to locate the main Wichita camp.

A week’s march from the Brazos the expedition was attacked by a band of warriors who led the Spanish into a trap. Following the war party, the soldiers came to the banks of the Red and a collection of huts surrounded by a stockade with a moat and well defended by the Indians who were flying a French flag. Mired in the sandy riverbanks, the Spanish sought to withdraw and consider the situation, but Indians, including some Comanche, armed with muskets and mounted on horses, cut off the retreat.

For four hours, gunfire rattled across the river. With darkness, Ortiz Parrilla managed to pull back to better ground, and then retire further to water and pasture. The Spanish pushed no farther, deciding to leave well enough alone. By October 25, they were back in San Sabá.

The set to at Spanish Fort marked two events that would play large in the future settlement of Texas. For the first time, the native tribes had been well armed with European weapons, and they were mounted. No longer did they need to stand aside in the face of European incursions.

The Spanish never would make any significant attempts to control or colonize the northernmost reaches of New Spain. In 1769, the lieutenant governor of the Natchitoches District visited the native villages along the Red and proposed that a mission be built among them, but it idea came to naught. The greater exploration of the Red and settlement of the land through which if flowed, particularly south of the river, would come with the Americans.