“He was just a local fellow who took pictures. He never really amounted to much.” If you asked the old men who gathered on the bench on the south side of the courthouse in Bonham in the 1950s to chew tobacco, whittle and tell the stories old men tell, that would have been their general recollection of Erwin Evans Smith.

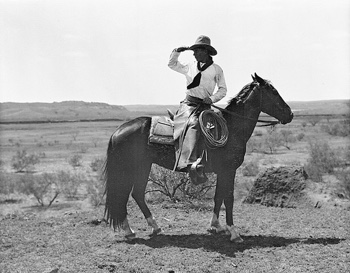

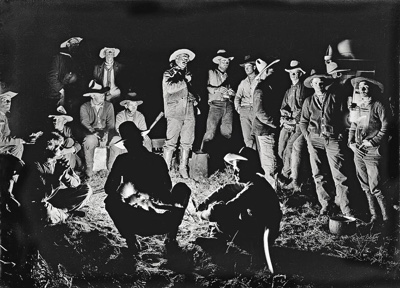

But there was more of course. With infinite patience and an Eastman screen focus Kodak camera fitted with a Goerz lens with a volute shutter, Smith captured the real image of that most universally recognized of American symbols, the cowboy.

That was not Smith’s intention, at least not in the beginning. He wanted to be a sculptor and reproduce the West in bronze, but he never quite got there, and somewhere along the way, the legacy he left was almost forgotten.

Smith was born in Honey Grove on August 22, 1886. Both sides of his family had come to Texas as part of the steady stream of settlers looking for a better life, the Erwins just after the Texas Revolution and the Smiths as some later time. Albert Smith had a mercantile store and his wife, Nancy, who had been sent east to a boarding school in Raleigh, North Carolina as a young girl, was educated and artistic.

Young Smith was four when his father died of pneumonia. Three years later, Nancy married Percy H. White, a merchant, and the family moved to his home in Bonham, the county seat. White was a pragmatic man, one who sought to give his family a comfortable and secure life, but who was willing to make allowances for—indulge is not really the right word—the less than practical leanings of his wife and stepson.

When he was eight, the boy made a trip to Foard County and the JCS Ranch owned by his uncle, John Sanders. As he trailed along behind his uncle and older cousin, he began to learn about the life—the real life—of the cowboy. The life, as Smith later put it, of “a man with work to do.”

Erwin Smith’s best boyhood friend was Harry Peyton Steger, a Bonham boy who as a man would become a leading figure in the New York publishing world. In later years, Steger would recall the pair galloping through the town on their horses, playing cowboys.

Before one of his summer trips to West Texas, Smith got a simple box camera and began taking pictures of the things he saw. He would bring the exposed film back to Bonham, where he learned to develop and print the pictures in a home darkroom.

At eighteen, he determined to take seriously his dream of becoming an artist, and went to Chicago to study under the tutelage of Lorado Taft, one of the leading sculptors of the time. After two years with Taft, Smith decided to continue his training at the Boston Museum of Fine Art, but the very thing he wanted to preserve with his art, the everyday life of the cowboy on the Texas range, was disappearing.

“I knew that the life wouldn’t wait, and that the technique would. So I put off Boston as long as I could,” Smith said, and went back to the West in 1906 to begin his work. It was not his intention to photograph the cowboys for sake of photography, but to use the pictures for reference later on. But in the long run of things, the end did not matter nearly as much as the result.

Smith latched on to the big outfits, riding the range with hands from the Shoe Box, the JA, the Frying Pan, the Matador, and the LS ranches. He worked the Palo Dura and the grassland along the Canadian river and spent time with the cowboys in Old Tascosa, a fading cattle town whose dusty streets had once been marked by the boot prints of Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, and Charlie Siringo.

His was not a labor with out danger. Once, he almost drowned trying to cross the Canadian during a flood, and he shared the same hardships and boredom that dogged the long days in the saddle and nights on the hard ground that marked the cowboy way. But still he took pictures and made notes and drew sketches with pad and pencil.

When the work on the range was done in the fall of 1907, Smith went to Boston and took up his studies again. He became friends with George Pattulo, a young Canadian who was the Sunday editor of the Boston Herald. Pattulo was taken by Smith’s photographs and used some of them to illustrate an important article in the paper.

Doctors had urged to Pattulo, whose health was less than robust, to leave the stress of the newspaper and spend more time outdoors. He seized on this advice to go west with Smith when the artist went back to continue his photography in the summer of 1908. Over the next few years, Smith and Pattulo moved between the western range and Boston.

Erwin Smith came home to Bonham in 1911, built a darkroom in the barn, weighed offers from five publishers to put out a book of his pictures, and took a stab at writing a novel. None of these ventures produced much income, and relations with his stepfather became strained. Eventually Percy White and Smith’s mother split up, so Smith, who had inherited land in Fannin County from his father, made various efforts to expand and improve his financial position, none of which worked very well.

Perhaps he had the artist’s disdain for the mundane, but for whatever reason, he never seemed to grasp the nature of his economic problems. There was always another idea, another plan, another project to divert his attention, and yet, somehow, things moved on.

Even after the family divided, Percy White had offered some stabilizing influence on the financial situation, but he died in 1916, just as a reconciliation seemed near, and the economic situation grew worse. In time Nancy sold the big white house in Bonham, and Smith’s property in Fannin County fell to foreclosure. All that was left was his infinite knowledge of the West and the cowboy, and his pictures.

From 1932 onward, Erwin Smith lived in a small house owned by his half sister Mary Alice Pettis. He ran a few cattle, puttered about, and looked after his mother. She died in February 1947, and her son followed her on September 4 of that same year.

When he died, it seemed that a life devoted “to make himself the full authority on the West and to record it truly in pictures and in statuary,” as Harry Peyton Steger once wrote, had gone for naught. But perhaps not.

In 1936, with the urging of a friend, J. Evetts Haley, Smith prepared one hundred prints for the Texas Centennial, and these works eventually found a permanent home at the Texas Memorial Museum at Austin. In 1949, Mary Alice Pettis donated more than 1,800 of Smith’s prints, plates and film to the Library of Congress, and in 1952, the University of Texas Press published book of Smith pictures entitled Life on the Texas Range. The photographs that accompany this article are from that book.

At his death, Erwin E. Smith was, in the minds of many as the old men around the courthouse in Bonham put it, “just a local fellow who took pictures. He never really amounted to much.” But there was more of course, so much more.

***

The originals of Smith’s work are now preserved by the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth. The museum has an extensive Web site, accessible to the public, with special material for teachers devoted to Erwin Smith and his photographs at http://www.cartermuseum.org/collections/smith/. The Red River Historical Museum in Sherman and the Fannin County Historical Museum in Bonham have collections of Smith prints and there are examples of his work in the Fannin County Courthouse.

***

The information used in this piece comes primarily from the introduction to Life on the Texas Range written by J. Evetts Haley.