by Edward Southerland

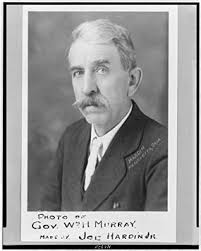

The community on the western edge of Grayson County was still called Toadsuck when William Henry Davis Murray came into the world on November 21, 1869. By the time the town got its new name of Collinsville, in 1880, Murray’s mother had died, his father had remarried and the family had moved on to Montague, Texas. At twelve, the boy left—or ran away from—home, and for the next seven years he worked as a farm hand and struggled to get an education.

After a smattering of public school squeezed into time off farming, he moved to Springtown, Texas, on the line between Wise and Parker counties, and entered College Hill Institute. On graduation in 1889, he taught school in Parker County and took up politics with the Texas State Farmers’ Alliance, an agrarian economic movement founded in 1875, and whose Parker County organization reached back to 1879. Murray also was an ardent supporter and campaigner for James Stephen Hogg when the latter ran for and was elected governor in 1890.

He also caught the attention of Mary Alice Hearrell, Johnson’s niece, and the couple married on July 19, 1899. They had five children, and their son, Johnston, born in 1902, was Oklahoma’s governor from 1951 to 1955.

In addition to acquiring a son in 1902, Bill Murray also acquired a nickname that would stay with him for the rest of his life. After his move to Tishomingo, the former farm hand had studied agriculture, and taken up farming again as an adjunct to his law practice. That year he was on the stump for gubernatorial candidate Palmer S. Moseley, and during his speeches, Murray often referred to the fields of alfalfa he was raising on his farm. A man who heard one of the speeches told the Tishomingo Capital-Democrat that he had recently seen “Alfalfa Bill” uncork a stem winder, and Murray was “Alfalfa Bill” from then on.

In 1903, a movement arose with the “Five Civilized Tribes” of the territory, as the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole were called, to organize a new State of Sequoyah in the Indian Territory. Murray and Charles N. Haskell were the only non-tribal members of the six-man delegation sent to represent the Chickasaw at a convention in Muskogee. Though strongly supported by the tribes, the idea failed when Washington insisted that the Territory and Oklahoma had to join the union as one state and one state only.

When an assembly met in Guthrie to write a proposed state constitution in 1906, Murray, representing District 104, became President of the Convention, which produced a document very similar to the one created earlier for the State of Sequoyah. Initially the proposed constitution had strong segregation and white-supremacy clauses supported by Murray, but which were opposed by President Theodore Roosevelt and did not make it into the final draft.

In the elections of 1907, Oklahoma’s first as state, Murray won a seat in the state house of representatives, and was chosen as its first speaker. He served only one term in the legislature, choosing not to run for a second term. He ran for governor in 1910, but lost in the Democratic primary. Then in 1912, he won one of the state’s three at-large seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. He won again in 1914 from the newly created 4th Congressional District, but failed to gain the nomination for a third term in 1916. Two years later, after a failed primary campaign for governor, Alfalfa Bill retired from politics and went back to the law in Tishomingo. In 1924, Murray and a group of Oklahoma ranchers headed to Bolivia to start an expatriate American colony. He spent five years in that South American country before moving back home to run for governor in 1930.

With Oklahoma hard into the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl starting to ravage the prairies, the voters were ripe for the strongly populist message advanced by Murray. His attacks on “The Three C’s—Corporations, Carpetbaggers, and Coons,” struck home, and Alfalfa Bill won the Democratic nomination while running up the largest voter majority in Oklahoma’s short history. On January 12, 1931, the man from Toadsuck took the oath as the ninth governor of the Sooner State.

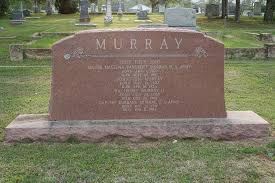

Murray ran for the state house again in 1938, but lost in the Democrat primary, and a try for the U.S. Senate in 1942 also failed. His wife, Mary Alice died in 1938, and became the first woman to lie in state in the Oklahoma capitol building.