For folks living in or near the Shenandoah Valley area of Virginia in the post-Civil War era, life was hard. War had left what historian C. Vann Woodward described as “the years of what would now be called ‘third-world’ poverty, stagnation, failure, economic dependency, and exploitation.” Such misery prompted many to leave for Texas and other parts of the country. While many individual southerners, white and African-American, were suffering, some industries were managing to rebound thanks mainly to the influx of northern money. Chief among them was the railroads.

Shortly after the Civil War, most rail lines through the South were relatively short and disconnected making seamless rail travel impossible. Business leaders like Pennsylvania’s Tom Scott bought up individual lines and connected them making rail travel easier. It was Scott and company that brought the Texas and Pacific railroad line to Fannin County in 1873.

Suddenly anyone wanting to leave the misery of Virginia to come to Texas could do so more easily.

That is what my maternal great-great-grandmother, Judith P. Wright, and her sons, James Edward (my maternal great-grandfather) and Thomas Henry Wright, did in the 1880s. They sold their Bedford County farm in Virginia and hopped a train to Fannin County. Their main reason for moving was the fact that relatives living in the Valley Creek area (at the time about halfway between Leonard and Trenton) had sent word that Texas was a good place to make a fresh start.

The first year or so was spent tenant farming on land near Red River. It was then that James Edward Wright met a gal named Ida Mae Medley who came to Fannin County from Carbondale, Illinois, by way of covered wagon. He fell for her because she was a good cook who made a great pan of biscuits, and she for him because he refused to touch whiskey. They soon married. The happiness of their new life was offset somewhat when James’s mother, Judith, died. While in Virginia slaves had done most of the domestic chores for her; therefore, she was ill- suited for the hard life of rural Texas and her health failed. Since the family lacked the money for a proper funeral, she was buried in an unmarked grave on land along the river; her burial spot remains unknown.

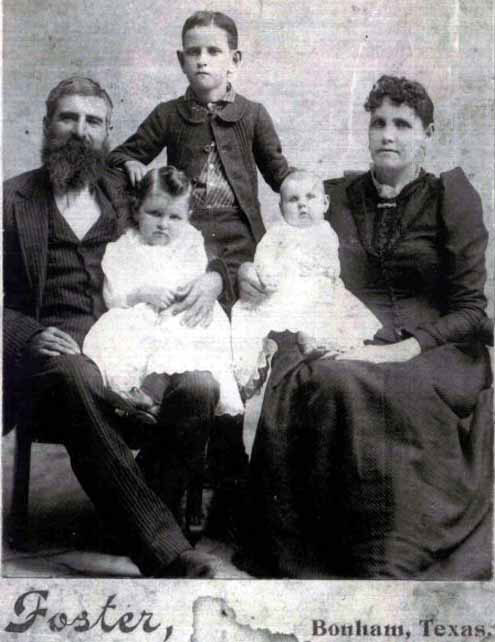

The young couple soon bought land in the present-day Elwood area, established roots and raised a family. My grandfather, James Henry Wright, was their first born. More children followed; it was the age of large families.

Thanks to the fact that the oldest daughter, Columbia May Wright, was interviewed on tape in late 1986 reminiscing about life on the farm at Elwood, at least some details remain. (May, as everyone called her, went on to marry a Mr. O.W. Bass and they eventually settled in Arkansas.) The typical farm life that she described is no doubt indicative of what rural life was like across Fannin County in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

She recalled the lean Christmas when the only gift her parents could afford to give the kids was a big bag of hard rock candy. She stated that her dad “felt awful bad about it.” To lighten the mood, he stepped out on the front porch with his gun and fired two or three shots into the air. He claimed he was shooting at Santa Claus for bringing no more than he did. “He had a keen sense of humor,” she stated.

Since it was the age before radios, stereos, or televisions, entertainment was homemade. Music in the home meant that someone had to play an instrument. She recalled that her dad had bought a piano and was pleased when her little sister, Cora, learned how to play it. “He loved music,” she stated.

For the ladies of the house, trips to Bonham, a seventeen-mile affair from Elwood by wagon, were few and far between. She recalled that she, her mother and the other children accompanied her father to Bonham no more than twice a year. Often the trips were to the general stores on the square so her mother could buy materials for sewing clothes and quilts. “She sewed everything we wore,” she stated. She laughingly remembered one such trip when her mother was under the assumption that her dad had earned some extra money from recently selling a mule. Once he noticed the yards and yards of material that she had gathered, he felt obliged to tell her, “Ida, now remember, I didn’t sell that mule.”

Church also played an important role in their social lives giving them such events as Sunday services, tent revivals and brush arbor meetings to attend. Sunday morning services were often a springboard to big dinners held afterwards. May stated that while most of the family was at church, her mother stayed at home fixing the big meal. “We never went to church or Sunday school in our life that we didn’t bring home two wagon loads of people for dinner,” she stated.

Perhaps one of the most exciting events of May Bass’s young life was the time the whole family loaded into the mule-drawn covered wagon and set out for Durant. The wagon and team of mules carrying the family had to ferry across Red River. She recalled that she, her siblings and her mother stood along the side of the ferry while her dad stayed up front with the mules lest they get spooked. When they reached the Oklahoma side they traveled through dense woods for a while before coming up on a beautiful prairie with tall grass swaying in the breeze. The beauty of it all was tempered a bit when her dad informed them that he thought they were lost. (No one likes being lost while traveling these days, but imagine being lost in a covered wagon!) Before long he regained his bearings and got them to Durant where they visited with relatives. Returning home meant another long wagon ride and another ferry trip across the river.

As time went on the Wright children grew apart and left home to begin lives of their own. However, they carried with them the memories of growing up on a farm in a rural setting.

In 1911, at the age of 62, James Edward Wright died and was buried in the Elwood Cemetery. Although Ida Mae Wright outlived her husband by 28 years, she never remarried. Why? I like to think it was because she knew deep in her heart that no other man would ever love her as much as he did.