Recap: In November, 1941, the War Department detached the 2nd Battalion of the 131st Field Artillery Regiment from their parent division, the Texas National Guard’s 36th Infantry, and sent them to reinforce the Philippines. Following the December 7 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, on the battalion was diverted to Australia and then sent to the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies.

On Java, the battalion served as a ground support unit for a handful of B-17s that had escaped destruction in the Philippines. When those planes were evacuated to Australia, the battalion stayed behind and took part in the short-lived defense of Java, fighting the Japanese invaders for eight days until the Dutch capitulated on March 8, 1942. The 534 men of the battalion became Japanese POWs. Jay Hoover, nineteen years old, was a PFC in Battery F.

*****

“After we surrendered, they [the Japanese] let us drive our own trucks up to a race track. We stayed there for a day or two, and then they took us out into the jungle, and we set up our own camp. The moved us again, after a few days to an old Dutch army barrack.”

This camp was in the seaside town of Tanjong Priok and was home to the POWs for about five weeks. From there the prisoners were moved inland, into the middle of Batavia, to a former Dutch army post called “Bicycle Camp.” Here the Texans of the 2nd Battalion met the survivors of the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30), sunk in the Sunda Strait on evening of February 28 – March 1.

“This is where we met the boys from the Houston,” said Hoover. “These guys hadn’t been issued any clothes and most of them didn’t have much to wear. Most of us had two suits, so we gave them a blanket or a pair of pants or something and shared with them. We all kind of came together as one in that deal.”

Houston’s sailors and Marines brought the American contingent at Bicycle Camp up to 904. There were about three thousand prisoners at the camp all told, the rest being remnants of Australian, British, and Dutch units that had surrounded or been captured during the early tide of Japanese successes.

At Bicycle Camp, the Japanese begin taking POWs out in small groups to work. “They started working us down at the docks, loading sugar and first one thing and the other, bound for Japan,” said Hoover. But the Japanese had bigger plans for the captive workforce, something considerably more impressive than loading sugar.

The soldiers of the Rising Sun were driving through Southeast Asia, with India as their goal. The 15th Imperial Army was in Burma where they were fighting for control of the jungle against British and Indian troops of General William Slim’s 14th Army.

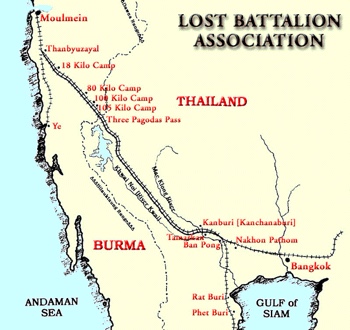

The Japanese supply route ran across the South China Sea, past Singapore and through the Strait of Malacca to Rangoon. It was long and dangerous and subject to interdiction by Allied submarines, so Tokyo dusted off an old British survey for a 260-mile railroad through the jungle from Thanbyuzayat, Burma to Ban Pong, Siam (Thailand). The British had deemed the road too difficult and too costly, both of treasure and human life, to build.

The Japanese felt no such constraints, and in September 1942, started moving POWs to the area. Japanese engineers, studying the British plans said it would take at least five years to complete the line. The Imperial Army allowed fifteen months, ordering the railroad finished by November 1943.

As the Japanese prepared to move their prisoners, they allowed each man to send a printed post card to someone back in the States. The cards gave little information save that the sender was alive and a POW. Until these cards begin arriving at their destinations, sometimes more than a year after they were turned in to the Japanese, no one in America knew exactly what had happened to the “lost Battalion,” and its men.

“The ship they hauled us in was a ship they hauled the cavalry in. From the floor to the ceiling was about eight or nine feet. They’d gone in a put a deck halfway and filled both decks with men. It was so tight we didn’t have enough room to all lay down at once and it was too low to stand up. I went down in the hole when I got on, figuring it was better to be down on the hay and horse manure than on the hard boards.”

It took five days to steam from Java, across the equator to Singapore, the first stop on the journey. After two days in Malaya they were back at sea, bound for Moulmein on the Burmese coast.

“One day they said they’d give us a bath. So here I am, covered with manure and hay and sweat, you can just imagine. We went up the ladder into the cold spray. I don’t remember where I got some soap, but I had some. Well, I got wet and then lathered down and they shut the water off. Now, instead of being covered in dry manure, I’ve got wet manure all over.

“When we got to Moulmein they put us in a funny looking place that had big concrete walls around it. Everything was concrete and the beds were steel and there was a guillotine in the compound. We figured it was a prison.

“Well, we final asked a native, and he said it had been a leper colony. That scared the daylights out of us, and we were glad to get out of there after a couple of days. They moved us up into the jungle, and we started building the railroad.”

Of the 904 Americans who had started out at Bicycle Camp in Java, 668 went to Burma to work on the railroad. Some POWs were lost when the ship taking them to Moulmein was attacked and sunk by American B-24s. Two hundred fifty-six men were sent to work details in Japan and other places in Southeast Asia and a few remained in Java at Bicycle Camp.

It was the railroad, brought to world renown by French novelist Pierre Boule in his 1954 book, The Bridge Over the River Kwai, and the David Lean, blockbuster film version three years later, which claimed the most men. One hundred thirty-three men of the 2nd Battalion died working on the railroad that over all, consumed sixty-nine men per mile of track laid.

“It was known as the ‘Death Railway.’ We built it from Moulmein, Burma to Thailand. They started on each end and built toward the middle. Most of the British were on the Thai end, and they’re the ones who built the bridge over the Kwai River.

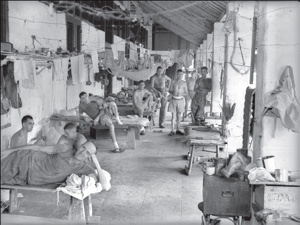

“During this time they worked the daylights out of us, underfed us, beat us and bombed us. The natives would make shelters out of bamboo poles and banana leaves and we’d move from camp to camp about every 5 kilos—three hundred to four hundred men per camp.

“They didn’t have too many guards, there was no place to go. No one could survive very long in the jungle. We had to take turns keeping the fires burning just to keep the animals out of the camps. Some guys found a fourteen-foot python in the bamboo one night. He was breakfast the next morning.

“Dogs would bring $25 if you could find one, and cats were worth six or eight dollars for something to eat. There was never enough food. The question each morning was, how many were dead?”

Jay Hoover and his comrades spent a little more than two and a half years working on the Burma-Siam Railway. He watched friends die around him on a daily basis. These were good men, who simply could take no more of the physical abuse and wearing of hunger and overwork and quietly died.

For a stretch of that time, Hoover was so ill with beriberi that he could not walk or drink water. He told of struggling into one camp and collapsing only yards from the mess tent. Had he fallen outside the camp the guards would have shot him.

“I couldn’t get up to eat. I just lay there. A friend came out with his cup of rice and offered to share it. I said no. He said, ‘If you won’t eat, I won’t eat, so we shared the rice and the next day I was able to go on.”

Another time he got into a confrontation with a guard who charged him with a bayonet. “He stopped just before it would have gone into me. I don’t know how he stopped. I don’t know why he stopped. The Lord was watching over me, I guess.”

Liberation came in August 1945, about two weeks after the second atomic bomb destroyed Nagasaki, Japan. “We didn’t know for sure the war was over, but the reaction of the Japanese told us something was up."

It was December before the survivors of 2nd Battalion returned home. They spent the interval between their liberation and their return being treated at various army hospitals and camps to bring them back to a semblance of heath. Hoover, who had weighted 176 pounds when he sailed from the United States, weighed about 100 pounds when his war ended.

Hoover’s parents had moved to Denison and he arrived there in early December 1945, home in time for Christmas. “His brother had been in the European Theater and was home too, and his sister gave a welcome party for them,” said Rita Hoover. “I didn’t intend to go because I had a boyfriend in the navy, but I was a member of the church with his sister and my mother convinced me to go.

“Jay and I were partners when we started playing forty-two and when the party was over he took me home. I either left my comb in his car or he took it, I don’t know, but he had to come back later to return it.” They were married on March 23, 1946. “He said if I’d marry him, he’d take me to Paris. I didn’t know there was a Paris, Texas. We got married at the First Baptist Church.”

When Jay Hoover’s war was over, like millions of veterans, he was not interested in retribution, revenge, or reparations. All he wanted was a chance to get on with his life. He worked at several jobs, although a heart condition, the lingering after effects of beriberi, making some types of work difficult though he was still a young man.

In 1952 he went to work for Poole Manufacturing in Sherman, selling their clothing line in West Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Colorado. “From the beginning I made more than they guaranteed me, so I was on trial with them for 25 years.”

The Hoovers moved to Vernon, and when their son and daughter left home, Rita decided she didn’t want to sit at home alone. “I went to some textile manufacturers and got them to let me sell their products in Jay’s territory. This worked so well, we started buying women’s clothing in Dallas and selling it directly to our customers. We bought one of the first commercial motorhomes and sold out of it. We called our company ‘Rita Hoover Wholesale.’”

The Hoovers traveled together and sold clothes for fifteen years. When the gas prices started to rise and Jay’s health made it harder for him to drive, they decided to retire. That was in 1973. Since they still had family in Denison and their children were living in the area, the moved back to the city to retire. Theirs is a remarkable story, of remarkable people, who see nothing at all remarkable in what they have done. Rita Hoover died in 2015.

Each August, the members of the Lost Battalion, including the men of the Houston, gather to remember their liberation from the hell disguised as the Burmese jungle. They are old men now, and for most, the memories of those times have ceased to color their dreams. Of the 904 Americans whose lives intersected at Bicycle Camp, 204 still answered the muster in 2000. In 2017 there is one.

The soldiers, of 2nd Battalion, 131st Field Artillery Regiment, 36th Infantry Division, Texas Nation Guard, the most honored unit in Texas’ long military history, and the sailors and Marines the USS Houston, the most decorated heavy cruiser in the annals of the U.S. Navy, were petty tough men, and a special lone star has long watched over them.

But then we know that, and in the quiet times, when they stopped and remembered, they knew it too.