It begins each year, as February gives way to March. The stirrings, dormant since the fall, are awaken by the promise of spring and the new shoots of green grass that start to push through the dead thatch.

It starts here first, in the south, where winter’s hold is never quite so tight as in other parts of the county. The lengthening days and wakening calls of birds, trip the inner circuits that have warmed the blood and quickened the pulse for more than a hundred years.

The very idea of its approach squeezes into narrow, rubbish strewn vacant lots surrounded by towering buildings in the cities, and flows out into the rural pastures where the grass is still cropped from its winter’s sleep. The response is in dabs and dribbles at first, a couple of boys, some teenagers, an older man whose memories encompass two score spring awakenings. All it takes is two. No, all it takes is one.

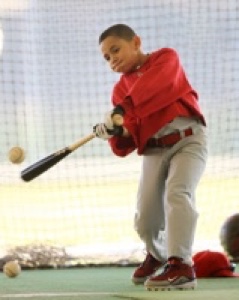

One boy with a bat and a ball and an imagination. He tosses the ball into the air, takes a mighty swing and tears off around a pretend diamond to score the winning run in a phantom World Series as the ball soars over the fence to the roar of the crowd. Baseball is back.

At its purest, the game is for kids in an empty lot, where play and practice are often interchangeable. “On your horse,” shouts the batter and the clutch of kids in the outfield stand ready to break with the hit. The batter tossed the ball up and lofts a long fly toward the fielders.

One, the one with natural instinct or maybe just a little more experience, is off in an instant, gliding over the ground watching, gauging, tracking the flight of the ball against a high blue sky. If he does it right, the ball and the fielder arrive at the same place at the same time and player snares the ball in his glove, spins and fires it toward an imaginary cut off man a half a field away.

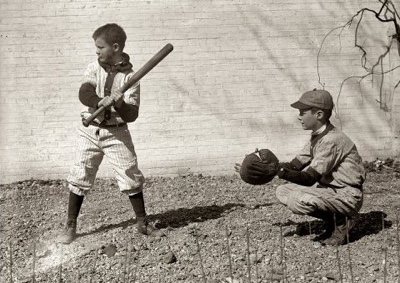

It a game of complex rules and simple execution. The kids choose sides. They toss the bat, carefully grasping the handle, fist over fist until it falls to the ground, to determine who is first up.

The losers take the field, covering the diamond as best as their numbers allow. It the sides are really uneven, then with an easy facility than shames the world’s diplomats, they negotiate a rule variation to accommodate the situation. “Balls hit to right don’t count,” or “Big guys have to hit lefty,” or “Little kids get to start at second if they get a hit.”

In baseball everybody plays. When his time at bat comes round, even the gawky, bumbling kid, relegated to far right field, the time-honored Elba of the less skilled, gets his cuts. If he makes contact, if it slips through the infield for a hit, he stands proudly on first base, having got there by the same means as Cobb and Ruth and Robinson. He stands redeemed.

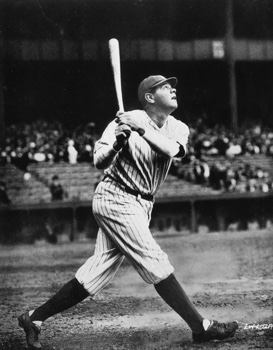

It is a game long on opportunity. With two strikes on the count and 35,000 Cub fans on his back, an aging Babe Ruth, gestures to the far reaches of Wrigley Field, and silences the crowds in two cities by powering Charlie Root’s next pitch into the center field bleachers. As he trots his familiar trot on spindly legs around the bases, he is vindicated.

It is a game where a misplay can last but a moment and be forgotten, or it can be engraved on the hearts of thousands. It is the slow, bouncing, jiggling ground ball off Mookie Wilson’s bat in the bottom of the tenth inning in Shea Stadium, that promises Boston its first World Championship in 68 years, until it improbably dribbles through the legs of first baseman Bill Bucker and into right field.

Even before salaries that resemble the gross national product of small counties, it was a game where the biggest were indeed bigger than life. When someone pointed out to Babe Ruth, that his salary was far greater than that of the president of the United States, the Bambino observed, correctly, “I had a better year than he did.”

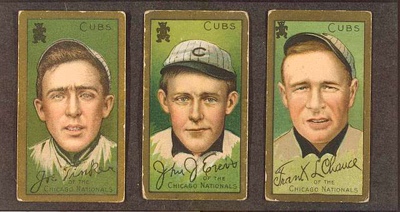

It is a game of epigrams. This by Franklin P. Adams in 1908 is with us still:

“These are the saddest of possible words

“Tinker to Evers to Chance”

A trio of bear cubs and fleeter than birds

“Tinker to Evers to Chance”

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble

Making a Giant hit into a double—

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

It refers, of course, to the infield combination of the Chicago Cubs, shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers and “the Peerless Leader,” first baseman Frank Chance. All three made it to Cooperstown in 1946.

It is game for all seasons. It fills our springs with expectation, our summers with excitement, our autumns with triumph and our winters with memories enough to last until the next frosty February gives way to the milder March and the cycle begins again.