It seems evident that by 1860 Robert H. Taylor’s political star was rising. In five elections in a row he showed that he had the trust of the voters back home. And the Cortina affair showed that he had won the confidence and respect of the state’s governor. It is not unreasonable to assume that he had the popularity and momentum, coupled with obvious personal ambition, to catapult him to a higher office, perhaps governor? US congressman? US senator?

Granted, it’s pure speculation, but history shows that a capable politician usually ascends to higher office if circumstances allow. For Taylor, however, circumstances did not allow. An event beyond his control loomed on the horizon, one that would ruin the best laid plans of many a mice and men. It was the Civil War.

As 1860 crawled along, it became clear to Southern leaders - namely politicians, business leaders and newspaper editors - that Abraham Lincoln was going to be elected President of the United States. To them this was unacceptable. In their eyes Lincoln and his party were rabid abolitionists. Never mind the fact that Lincoln and the Republicans did not run on a platform calling for the immediate abolition of slavery. The mere fact that Lincoln had criticized slavery in previous speeches convinced them that he and his party would destroy slavery, or at the least foment a slave rebellion.

Perhaps no one said it better than historian Don Fehrenbacher when he wrote, "what proved to be crucial in 1860 was not the true nature of the Republican party, whatever that may have been, but rather, southern perception of the party as a thinly disguised agency of abolitionist fanaticism."

To Southern leaders the choice was clear: If Lincoln is elected, we must secede and divide the nation.

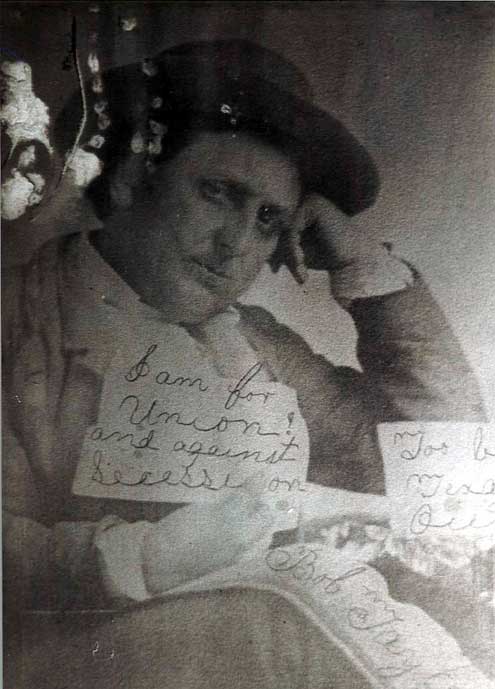

For some, the idea of a divided nation wasn’t troubling. However, for Sam Houston, Robert Taylor and a few other Texas politicians the idea was unthinkable, regardless the reasoning. They set about trying to head off the disaster. In so doing they ran the risk of being labeled pro-Lincoln, anti-Confederate or anti-slavery. The last label in particular made little sense with reference to Taylor. Fannin County census records clearly show that he was a slave-owner, having seven in 1850, and five in 1860. Moreover, page 196 of Deed Book H in the Fannin County Records room shows Robert H. Taylor buying a male slave, age ten, named Joseph from the trio of Benjamin White, John P. Simpson and Bailey Inglish. All of this is hardly indicative of someone opposed to slavery. However, it is possible that Taylor was a slave-owner who nonetheless had mixed feelings about the institution, and he probably lost no sleep over its ultimate demise.

One of the first moves among prominent Texas politicians hoping to avoid secession was to encourage Sam Houston to run for president on the Democratic ticket. Houston, they felt, might be the one person capable of holding the Union together. Referring to themselves as the "National Democracy," they held a mass meeting at Buass Hall in Austin on March 20, 1860. Many of the speakers called on Houston to run for president. In her biography entitled Sam Houston: The Great Designer, historian Llerena Friend wrote that one of the speakers was "Robert H. Taylor of Fannin County" and quoted another source as writing that Taylor "concluded with a soul-stirring eulogium upon Gen. Houston and the avowal that he was ready to advocate him, as the embodiment of conservatism for the Presidency." Despite all efforts, Houston declined to run with the Democrats.

Houston did, however, seek the presidential nomination of a new party, the Constitutional Union Party. He lost the nomination to John Bell of Tennessee. It was Gov. Houston’s last stab at trying for the presidency, no doubt to the disappointment of Robert Taylor and other Houston supporters.

Without Houston to campaign for, Taylor apparently threw his support to John Bell. In his book on the Great Hanging at Gainesville in late 1862 entitled Tainted Breeze, historian Richard McCaslin writes: "North Texas leaders who campaigned for the compromise-minded John Bell of the Constitutional Union party, such as Benjamin H. Epperson and Robert H. Taylor, were harassed at speaking engagements in Sherman and Dallas . . . ."

Bell’s race ultimately was a losing effort.

John Bell’s lack of success, coupled with Houston’s abandoning his run for the presidency, did not signal an end to anti-secessionist efforts. Even after southern states starting leaving the Union following the November election of Lincoln to the White House, Robert Taylor and others held firm. When some Texas leaders called for a secession convention in Texas, Gov. Houston refused to call one. Other leaders in the state called the convention anyway. Never one to give up easy, Houston ordered a special session of the legislature in an effort to block it.

It was during this special session that Robert H. Taylor gave the speech of his life. It is not an exaggeration to say that he put everything he had into a lengthy speech - roughly 4,700 words long - outlining why the state of Texas should not have a secession convention. Read a few sample quotes and you get a feel for Taylor’s passionate desire to stop his adopted state from leaving the United States:

On the issue of the anti-secessionists being in the minority: "Ten righteous men were required to save Sodom. There are fifteen of us; we have the courage and are capable of resisting this outside pressure - this unholy scheme to destroy the best government under the sun. We know today that we risk all, so far as we are concerned, but the stake we play for is worth the hazard. The Union! Oh, the Union!"

On the ultimate outcome of secession: "[I] believe that secession will bring war . . . ruin, bloodshed, anarchy, despotism and every other ill now unknown to us, the happiest and best contented (until lately) people on the earth."

On the secessionist leaders in Texas: I fear they will hang, burn, confiscate property and exile any one who may be in the way of their designs. They are but men and subject to all the infirmities of our nature." (This statement in particular could have caused Taylor some real problems back home inasmuch as two of the delegates who would vote in favor of secession at the upcoming convention were prominent Fannin County citizens Gideon Smith and Elbert Early.)

On being called traitors for Lincoln: "But we are told that we are traitors to submit to Lincoln. We are not submitting to Lincoln; we are submitting to the Constitution of our country."

On secession itself: "I’d vote against it all, if I were the only man in Texas that would."

Taylor basically concluded his remarks by saying: "I have spoken warmly because I have felt the importance of the question. I hope I have met it as one who dared to assert his opinions, fearless of responsibility. He who would do less is unworthy to represent my people."

Despite the best efforts of Taylor and those who agreed with him, the legislature voted to recognize the secession convention, basically giving the green light to secession.

It should be noted that the secession debate was not utterly void of humor. At one point a group of anti-secessionists held an impromptu meeting in the Senate chamber. Andrew Houston, Gov. Houston’s son and forever the prankster, spotted "a key dangling from the door of the Senate chamber," writes Houston biographer James Haley. After pushing the door to, he locked it and made off with the key. Haley describes the scene: "No one was the wiser until the senators began calling for help from their windows to the street below. An amused crowd gathered and began heckling the trapped and increasingly hungry legislators. ‘Hey, there, Taylor,’ one called up at Robert Taylor, a Unionist from Bonham, ‘we got you constitutional pie eaters where we want you now!’" According to Haley, Houston later remarked that "he had not managed the legislature with anything near the generalship shown by his Andy."

The secession convention convened on January 28, 1861 and adopted an ordinance of secession. They did, however, agree to allow the voters of Texas to have a say on the secession question. This provided anti-secessionists one last opportunity to sway public opinion against leaving the Union.

Anti-secession leaders met and wrote a broadside entitled Address to the People of Texas in which they once again listed their many arguments against secession. Among signers of the broadside from the north Texas area were Emory Rains, James W. Throckmorton, and Robert H. Taylor.

In addition to signing the Address to the People of Texas, Robert Taylor apparently hurried home to try to sway voters against the secession ordinance. The authors of Murder and Mayhem, a recent book on Civil War events in north Texas, write that Taylor "made impassioned appeals to his constituents, asking them to stay true to the Union. He, and others like him, succeeded. Fannin’s people voted against secession by a majority of 656 to 471."

Unfortunately for Taylor and his fellow anti-secessionists, Texas voters as a whole overwhelmingly approved secession. On March 2, 1861 Texas officially left the Union, becoming the 7th state to do so.

1861 was no doubt an agonizing year for Robert H. Taylor. On the one hand he was surely sickened over Texas leaving the Union. On the other he had pledged in his monumental anti-secession speech that he would defend Texas if her voters approved secession at the ballot box. In an eloquent flourish reminiscent of a 19th century politician, he stated that "their God shall be my God, their house my house, their destiny mine, and when they shall have spoken fairly at the ballot box, I am with them through good or evil report, and then this good right arm, which has never refused its country’s call, shall be among the first to repel foreign invasion or domestic violence." He now was obligated to fight for a cause that he obviously had little faith in.

According to historian Robert Weddle’s book Plow-Horse Cavalry, Taylor was initially on the muster rolls of the Stanley Light Horse volunteers, formed on July 6, 1861, as a private. Weddle writes that Taylor raised "three regiments for the Confederacy. The first, the Twenty-Second Texas Cavalry, was recruited from Fannin, Grayson, Collin, and surrounding counties." If I read Taylor’s Civil War service record correctly, they were enlisted at Honey Grove on Dec. 17, 1861.

Taylor’s service record further shows that he, and I’m assuming the Twenty-Second Cavalry as well, was formally mustered in at Fort Washita (located northwest of Durant) on January 13, 1862. At that time Taylor was promoted to the rank of colonel. His many duties kept him busy between Forts Washita and McCulloch (north of Durant).

As the war dragged on, Taylor eventually found himself headquartered back at Bonham. General Henry E. McCulloch, commander of the Northern Sub-District of Texas, needed help in trying to get deserters and draft-dodgers out of the thickets in the Fannin, Hunt and Collin county border areas. Chief among those who Gen. McCulloch wanted out was a Unionist named Henry Boren. In their book entitled Brush Men and Vigilantes, Judy Falls and the late David Pickering write: "Early in the fall of 1863, General McCulloch sent two Confederate officers who had opposed secession, Col. Robert H. Taylor of Fannin County and Maj. James W. Throckmorton of Collin County, into the brush to talk to Boren." Taylor and Throckmorton were unsuccessful because Boren refused to accept Gen. McCulloch’s terms.

Exactly what Colonel Taylor did in the war from late 1863 to its end in April 1865 is unclear because his Civil War service record is short on details.

Once the war ended, Robert Taylor did exactly what you would expect from someone who opposed secession in the first place, he dedicated himself to getting Texas readmitted to the United States as soon as possible.

Just three months after the ink had dried on the surrender papers at Appomattox, Taylor and other north Texas leaders, some of whom had signed, as did Taylor, the anti-secession Address to the People of Texas, met in Paris on July 17, 1865 "for the purpose of making known to Reconstruction authorities ‘our willingness to submit to the constitution and laws of the United States, and to ask the privilege of regulating our state government at an early day, and thereby reestablish order in society.’"

Tim Davis teaches at Bonham High School.