She mattered

Red roses…white corsages…and restaurant reservations. That’s Mother’s Day in the 21st Century. But people who have lost their mothers awaken each Mother’s Day with a melancholy blink.

Recently, I took a mental time-out and strolled through the beautiful and historically seductive Willow Wild Cemetery. Every delicate and respectful step I took made me realize the infinite number of mothers who occupy the cemetery’s nearly 10,000 graves.

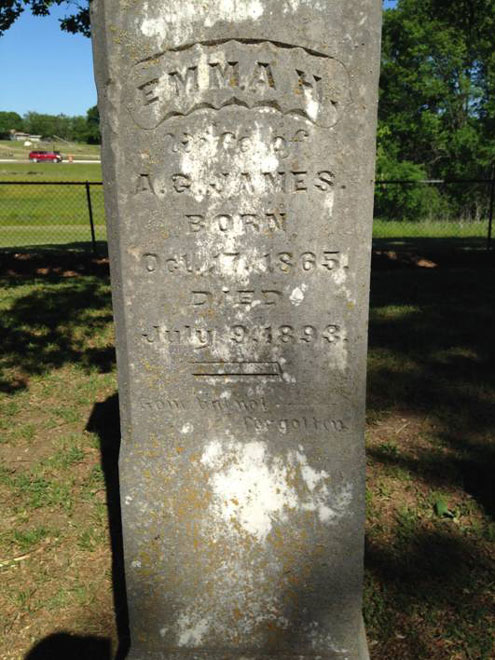

One timeworn, patina-kissed tombstone tugged me closer. It was that of Emma James. Her 19th Century upright gravestone stands tall and slender beneath a massive oak tree on the east side of the cemetery. I asked myself, “Were you a mother, Emma?” Then I glanced to Emma’s left and found the three-part answer---Alberta, Hampton, and Everett.

Many, many, many of us have outlived our mothers. But outliving children must, indeed, be a suffocating heartache. Emma did . . . but not for long. At the age of 21, Emma gave birth to a baby boy---Everett---on December 23, 1886. One year later, Hampton was born. In less than three years, she gave birth to Alberta, probably named after Emma’s husband, Albert James. I remember well the memories of having two little rough-and-tumble boys and finally welcoming a frilly little girl to the family. The joy Emma must have felt! Until…

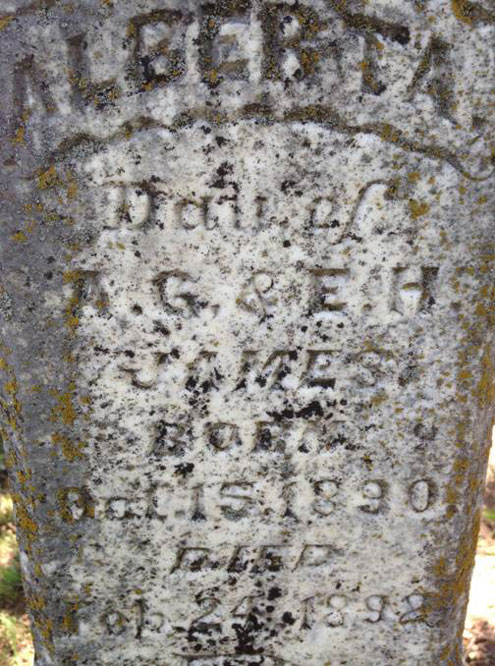

Emma and Albert lost little Alberta at 14 months old on February 24, 1892. Her headstone reads “Beloved one…farewell.”

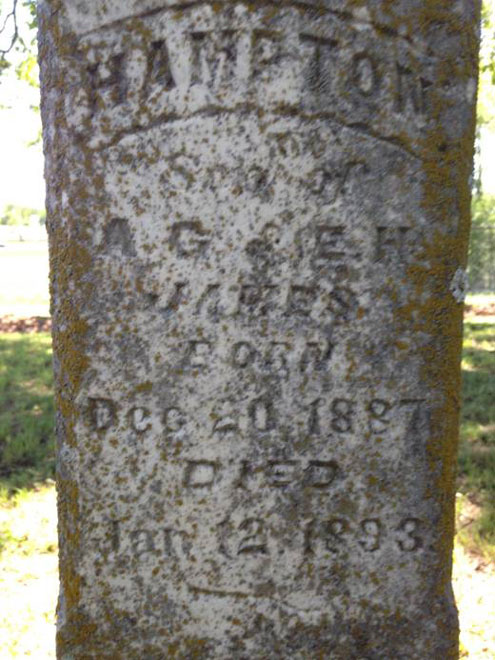

In less than a year, Emma said goodbye to her younger son, five-year-old Hampton, on January 12, 1893. His inscription reads “How many hopes we buried here.”

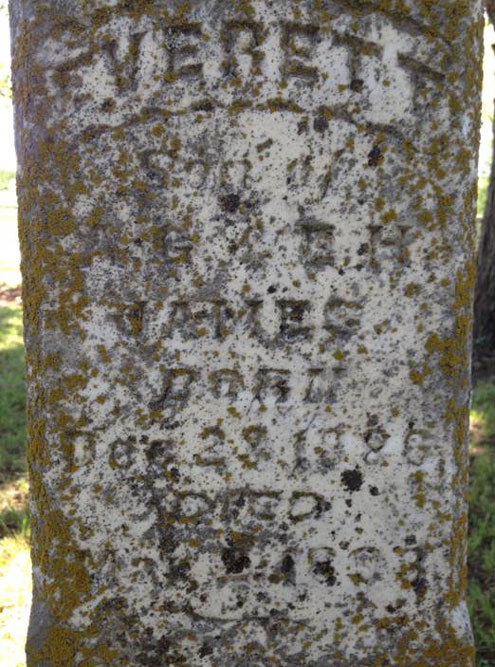

Twenty-one days later, on March 2, 1893, six-year-old Everett died. His gravestone---“Weep not. He is at rest.”

And finally, Emma died four months after that, on July 9, 1893. She was 28 years old. Her tall stone, which reads, “Gone but not forgotten,” stands stately under the oak tree and towers above her three children’s upright, yet smaller, markers. Albert died on June 4, 1902 at the age of 48.

It’s as if she’s still proudly mothering her children, ensuring that they are well mannered, standing erect and, yet, staying within hugging distance.

What happened to Emma’s children? In The Lonesone Plains: Death and Revival on an American Frontier, Louis Fairchild, says, “Child mortality was a 19th Century given, so fear of losing children was not an unknown or idle emotion.” Also, he said, “The frontier drew heavily on the infants, and every old graveyard offers waves of brothers and sisters.”

Like today, there are many causes of children’s death. In the 1890s, children were injured or killed, simply from jumping off or onto moving wagons. They would stumble, lose their balance, or their clothing would snag on part of the wagon, thus causing an irreversible tragedy. They were knocked down and hurt by loose livestock, or they brushed too close to a tethered mule or horse. Kicks could kill. Louis Fairchild wrote: “Range cows were more dangerous and unpredictable than a grizzly.”

Children choked on everything from a collar button to a cottonseed. They were scalded by water tipped off the stove or poisoned by a swallow of kerosene, used to light the stove. At times, they fell into cauldrons of boiling water or tripped into raging fireplaces and campfires. Snakebites could be fatal, too.

Parents suffered the loss of their children to punctures from rusty nails, a dragging nightgown ignited by flames from burning trash, the bite of a tick, or the glancing blow from an ax. Children met death from a long fall from a windmill, a rabid polecat, the flash of lightning, or a rattlesnake slipping under the warm covers at night.

“The Dangers of Childhood” from The Trail End Historic Site of Sheridan, Wyoming, states, “In the late 1800s and early 1900s - before the development of antibiotics and disease-specific vaccines - parents feared a wide variety of childhood diseases: measles, mumps, smallpox, chickenpox, diphtheria, whooping cough, scarlet fever, poliomyelitis and more. In 1900, 61 percent of the children who died in America perished from communicable diseases. These diseases would often strike with a speed and virulence that seems amazing to us today.”

Further, the website says, “If they survived infancy, children still had to fight to survive: at the turn of the century, 20 percent of the nation's children died before the age of ten. Most were victims of contaminated water, unsanitary living conditions, unpasteurized milk and poor nutrition, as well as contagious diseases.”

Trips to the cemetery meant cushioned comfort mixed with waves of grief. The Trail End Historic Site also tells the story of loss: “After Hazel died in December 1892, Ida and her husband Charles were nearly inconsolable, as Ida told Eula in May 1893:

‘We were out to see the little mound yesterday. The lot had been sown and graded, so I suppose the grass will soon be up. Poor papa; he walked up and down crying like his heart would break. It almost kills him to give her up. The little darling was always at his heels. Oh! How are we to live without her?’

Like most women who had lost a child, Ida hid her grief and told few of her deep anguish. She was able to share some of her feelings with Eula, however, who had been like a second mother to little Hazel:

‘There is a pang in my heart that nothing can take away and as the months wear on, the dreaded thought of a year having come between me and my angel almost kills me at times. There are very few nights my head is laid upon my pillow that the heart does not ache to burst. I say nothing and no one knows my feelings. I stand and look at the children as they come and go to school and I find myself saying, "Oh God, why did you take my Baby." The outside world thinks perhaps my grief grows lighter but to me it has been unusually heavy the past few weeks. The only way I can bear it is to look at friends who have gone through the same and say it is natural we should die.’”

The following “Mothers with Angels” poem, written by Sherri Shreela on the website www.angelfire.com, made me think of Emma James. As it notes---Sherri is the mother of children of Heaven---Joseph, William, and Julissa.

My Children are in the Other Room

My children are in the next room,

but I can't get to that

room till I am allowed.

But whoever is taking care

of my children is the best

babysitter ever, so at least

I don't have to worry too much.

I miss being able to go into that room.

But, sometimes I can hear

my children giggling and speaking,

barely though, and I have to

tilt my head just so,

and then I smile with a warm heart

from the sound of my children's voices,

knowing that my children

are having fun where they are,

till I get to go into the room

after I have finished

my work for the Lord.

Emma James was allowed entry into that room. Although you and I have many unanswered questions about Emma’s family, we do know this on Mother’s Day:

She mattered.