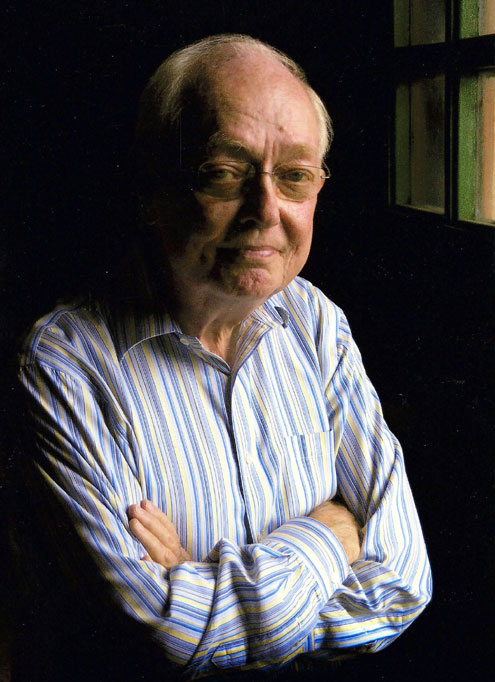

This project is dedicated to my friend and mentor, the late Tom Scott. Harry Peyton Steger is yet another example of local history, much like legendary jazz guitarist Charlie Christian, that would have slipped away forever if not for the keen perspective of Mr. Scott.

As local businessman Jack Lipscomb observed, "Bonham's historic hard drive crashed when we lost Tom."

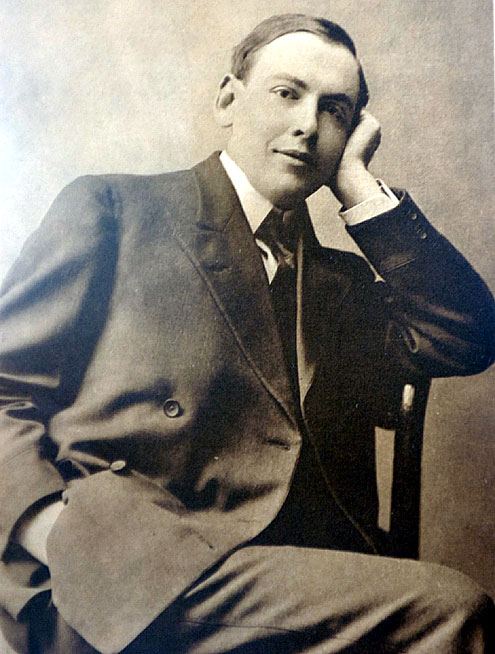

I can still see Tom leaning back in his swivel chair behind the desk at Fannin County Museum of History and pointing over his shoulder with his thumb in an attempt to direct my attention to a photograph of Steger on the wall behind him.

"You need to do something about this guy," Tom would say about Steger.

He was right, too.

Even when I realized Tom was handing me one of the best unwritten chapters in Fannin County history, I was still only looking at the tip of the iceberg. Bonham Public Library allowed me to study a collection of Harry Peyton Steger's letters that the Ex-Students Association of the University of Texas had compiled and my intention was to churn out a brief 300-word article about a Bonham boy who had been a Rhodes Scholar and, eventually, the editor and friend of legendary short-story writer O. Henry.

At that time, The short story of Harry Peyton Steger seemed like an appropriate title. Forty-nine chapters later...maybe not so much.

I started writing that first night and I vaguely remember glancing up at the clock. It was 3:00 a.m., I had about 800 words typed up and hadn't even gotten through the foreword of The Letters of Harry Peyton Steger 1899-1912.

Although I wasn't even to the book's introduction yet, I knew our boy Harry had entered UT as a 15-year-old (having donned long trousers especially for the event, he noted), won the Cecil Rhodes Scholarship in competitive examination, been elected president of Oxford's largest debating club, tramped across Europe, was sent to Monte Carlo for the London Express and had been arrested by the Italian Army (most of it, he added, tongue-in-cheek) for building a wind-whistle on a rock in the Mediterranean Sea.

I should have changed the title right then, because Harry hadn't yet thrown away his Rhodes Scholarship, spent 16 days begging his way from Queensboro to London penniless in order to write a series of articles about the plight of the unemployed, not to mention hiking and biking across Europe with old college pal Roy Bedichek before they both scraped together just enough money to scramble aboard a tramp steamer bound for Quebec. Steger would arrive in New York City (and shave at once, he recalled) with little money and no promise of employment.

In two years Steger would be working his way into the position of literary advisor with Doubleday, Page & Co. and naively coaxing a reluctant O. Henry into doing a little publicity work.

What could it hurt?

A lot, actually.

It troubled me that Harry had relinquished his Cecil Rhodes Scholarship, enough so that I went to talk to Tom Scott.

"There comes a jumping off place, Allen," Mr. Scott told me. "Harry was only 25, but you have to understand he had been in college, what, about 10 years, maybe? There comes a point where you realize you may have taken enough from the educational process to actually begin applying what you've learned."

Tom had also told me that Harry's tombstone in Willow Wild Cemetery had an epitaph written by Pulitzer Prize-winner Booth Tarkington. I found the tombstone, but sans inscription and I came back to the Fannin County Museum of History to tell Mr. Scott that perhaps he was mistaken.

"Oh, hell!" he growled. "Go home and mix up one part bleach to four parts water and come back and get me."

In 30 minutes, Tom and I were looking at a horizontal concrete slab over the Steger gravesite and the slab was covered by an inch-thick layer of lichen and grass clippings. The bleach helped dissolve the moss. A hoe scraped off the resulting sludge to reveal the epitaph Tarkington had written to Harry's dad, Thomas Peyton Steger.

Tom was shaking his head.

"But there it is," I said.

"It's not the phrase I thought it was," Mr. Scott replied.

"But it matches what I've read in Harry's letters, so we're on track," I offered.

We both shrugged as if to say, "Hey, it is what it is."

In addition to Tom, this project could never have happened without the ladies at Bonham Public Library. Whatever information I truly needed, they came up with it.

Barbara McCutcheon had The Letters of Harry Peyton Steger patiently waiting for the chance to come to life. She compiled the chapters as this story unfolded and also found a haunting photo of Charlie Thurmond. Charlie was a friend of Harry's and a Vasser girl reared on West Fifth Street. Their fathers operated Thurmond and Steger Law Firm, which was where a young Sam Rayburn, fresh out of college, worked to meet the requirements needed in those days to become a lawyer.

Charlie's photo came from a passport signed in Grayson County by Winnie Jones, Deputy Clerk of the U.S. District Court in Sherman, Texas. It was 1920 and Charlie was on her way to spend the summer in Italy, France and Belgium. Those were the days, my friend.

Debbie Green found several historical facts, including transcripts from when Harry's uncles in Bonham had been subpoenaed to testify before congress after a contract to supply mules to the U.S. Army came up lame. Best I can tell, the Steger Mule Syndicate got caught between a rock and a hard place. The boys had to decide between contributing to the politician that had originally greased the government wheels to enable the contract or pay off their business partner. It probably didn't take long it to figure out it would be better to face all of congress than face the wrath of Congressman Joe Bailey.

For 18 months, whenever I was stumped, I took a stool at Bonham Public Library and I usually had the answer before I got up.

Arlene Moore provided the most likely scenario behind Harry Peyton Steger's irrational behavior in his final hours and the story would have been vastly inferior without her many contributions.

I want to also thank Tammy Skidmore Rich for being the first person to recognize this was more of a book than a column and for helping me locate the final will of Harry's father. I saw a lot of my own father in the pragmatic behavior of Bonham lawyer Thomas P. Steger as he tried to explain the ways of the world to an idealistic son busy "chasing butterflies."

Tom Scott and I discussed this passage at length without coming to agreement. Tom said Harry was referring to literary adventures.

"I don't know, Tom," I wondered aloud. "Seems to me he may mean two-legged butterflies."

Losing his only son had taken the wind out of Thomas P. Steger's sails, but he stoically went on. Then, in the spring of 1931, his wife died. When Thomas made out his will, he left his money pistol to a grandson. Thomas asked that as little notice of his death as possible be given and he didn't even want a headstone. I guess his last request was to simply be laid to rest beside his son. Then he went home and put a bullet through his heart.

Another person who encouraged me more than he knows is Dr. Pat Taylor, who, like Harry Peyton Steger, is an accomplished graduate of Bonham High School.

"This should be a screenplay," Dr. Taylor wrote me early on.

He's right, of course. I just don't know how to get Larry McMurtry to develop the script and Leonardo DiCaprio to take the lead role. At one point I wondered about attempting to secure a J. Frank Dobie Fellowship and spend a year on Dobie's ranch putting this project together correctly. But The short story of Harry Peyton Steger was all made possible because the businesses in Bonham have allowed North Texas e-News to be a part of this community for more than 12 years. I would never let them down and let go of something so many people have worked so hard to build, story by story, concept by concept.

As was the case with Harry Peyton Steger, Bonham is the place I have always been proud to call my hometown. And I'm proud that small towns in Texas still turn out humble, respectful, intelligent young men that can compete anywhere. At every Bonham High School graduation, I catch myself thinking that any one of a number of our young men and women may very well be our next Harry Peyton Steger.

And I would be remiss if I didn't express sincere appreciation to my brother, Mark, for adding a little Rich family perspective to the Steger family saga.

Early in this project, I admitted to being more than a little intimidated at the fact that one of the poorest students in Bonham High School history was undertaking the life story of a Rhodes Scholar, perhaps the most gifted intellectual BHS ever produced.

"Now, now, you're being way too hard on yourself," Mark consoled me (I think). "That pretty much shows the way things have gone around here."

That wouldn't be so funny if he wasn't so right.

Don't forget this all started with a 3x5 card on the wall of Fannin County Museum of History. It may have been the first 3x5 card I ever studied. My guess is the card is still on the museum wall and all 49 chapters are right there on it if you squint your eyes and look hard enough.

If there was one particular moment of enlightenment during the past 18 months, it was that some of the men I hold in great esteem---in particular John Lomax and Roy Bedichek---remembered a guy from my hometown as the very best of their generation of UT graduates...our boy, Harry.

If I was driven by one underlying cause over the course of this project, it was that maybe Harry's hometown should remember him, too.

I have saved a few of my favorite stories for the faithful followers of The short story of Harry Peyton Steger. The first ones come from playwright Montague Glass.

Harry had told Montague that he was fond of the young of all species, but "particularly cats and authors." The bills that came from feeding both were staggering.

It seems that one night after enjoying an evening of theatre in New York City, Harry and Montague were walking past the Verdi monument at Broadway and 71st Street when the mournful mewing of a discarded kitten froze Harry in his tracks.

Montague watched as Harry scrambled around the monument until the kitten was located.

Cuddling his new friend, Harry exclaimed, "Now...we're off to find a dairy!"

At midnight, none of the posh establishments nearby remained open, so the two men ambled 10 blocks with the hungry kitten twisting and turning in Harry's pocket before, at last, strolling into an open diner.

"Say, what would you have that would be good for a starving kitten we just found?" Harry asked the owner.

"Smoked sturgeon," the man replied, not missing a beat.

"Hey, then I'll take ten cents worth," Harry replied.

The proprietor fixed his gaze on Harry for a moment and said sternly, "C'mon, who's gonna sell ten cents worth of sturgeon? Best I can do is twenty-five cents for a quarter of a pound."

"Fire away!" Harry answered as he set the squirming kitten down on the floor of the diner.

The hungry little feline devoured the fish and frantically searched for more, so Harry coughed up another two bits for a second helping.

Just as that delicacie, too, disappeared, a fellow who appeared to be a regular customer walked in and casually ordered a bottle of milk. The proprietor promptly obliged and Harry had a puzzled look on his face as he watched the customer disappear out the front door.

"OK, wait a minute," Harry said as he turned back around to face the man running the diner. "Are you telling me you think smoked sturgeon is better for a little kitten than milk?"

"What do I look like...a cat doctor?" the proprietor sneered.

Harry picked up the kitten and started for the door.

"Look, mister," the man said, softening his tone a bit as he savored his last minor victory of the day, "just be glad that wasn't a puppy you picked up. I'd a' stuck a sucker like you with a $5 chunk of Westphalia ham."

Harry would have shrugged off the exchange as an unpleasant business deal with an unfortunate fellow of inferior breeding. If you know better, you do better and gentlemen knew better than to take advantage of any one of God's creatures, two-legged or four-legged.

Besides, fifty cents of smoked sturgeon was nothing to a man who often had almost that many people out to the bungalow in Freeport for dinner and conversation. His wife, Dorothy, remarked to her family that she had no idea how many people to expect until the caretaker began setting out chairs.

Here is how Montague Glass described an evening with Harry and Dorothy:

There I have met every condition of author,---authors for whom the American publishers were fighting like terriers over a choice bone, authors whose youth and inexperience never found their way past the outer office-boy of a magazine or publisher's office,---fiction writers, poets, historians and scientists and all of them unaffectedly enjoying themselves. There was something about Harry's mere presence that banished affectation and made even the writers of best sellers unbend and become as human beings. Nor did anyone talk shop at these gatherings.

"The danger of sitting down 13 to a table," Harry said one Sunday, "is that somebody's bound to break a glass over just how much a word Robert W. Chambers gets for his stuff."

There was, however, little chance of 13 at Harry's table. The number was more often twenty and over, with Harry at the head seated in an armchair---a black cat and a white cat cradled in either arm.

Corra Harris summed up Harry's character in one phrase.

"He had a sweet soul," she wrote me.

And I can say no more than that.

-- Montague Glass

In "Out of the Old Rock," J. Frank Dobie had a humorous recollection of a conversation between a young Harry Peyton Steger and Roy Bedichek.

In the vigor of early manhood Bedi drank some whiskey---maybe not too much---although after he married, any drinking was bad economically. I don't think he ever loved any man quite so much as he loved his college friend Harry Steger, with whom he bicycled through Europe and who died young. He cried all day long, so Mrs. Bedichek has told me, after receiving word of Steger's death. One of his favorite anecdotes was of meeting Steger on Congress Avenue in Austin one day. They both wanted a drink but before entering a saloon swore to each other that they would take only one and then get out. They took the drink, and it was good.

"Well, let's go," said Bedi.

"That drink makes me feel like a new man," Steger said, "and now the new man has to have a drink."

I never did ask Bedi if he joined the new man.

-- J. Frank Dobie

Maybe the most beautiful surprise as I put the previous 49 chapters together was an email that made its way to my farm in rural Texas from New York City.

I came across your article today online and was very interested.... you see my great-aunt "Dolly" McCormack was Mr. Steger's wife at the time of his death. Is there anything in his letters about a wife & son? My grandfather talked about her often to me as a child, but I have not been able to find any information on her. He claimed that she was an actress in silent films, that her first marriage to a wealthy NYC heir was annulled by his parents...I am the one who found evidence of this marriage in the New York Times archives. I cannot tell you how excited I was to have at least one of the stories of his beloved sister confirmed. I Google Mr. Steger every few months just to see if there is anything new listed for him and that is how I found your article. I have two pictures, prints actually, hanging in my dining room that, according to my grandfather, hung in Dolly and Harry's home!

That email came rather early in this project from Dorothy (Dolly as her family called her) Steger’s great-niece, Jan Massey. I raced to tell Tom Scott.

“Harry had a son?” we both wondered aloud.

Well, not quite. The best Jan and I can determine, Teddy Steger was about two years old when Harry and Dorothy married, although the McCormack family always just assumed it was Harry’s child.

After Harry died, Dorothy temporarily left Teddy with her family in New York and moved to California where she married a Hawaiian man named Jack Ena. Thanks to the research of Jan Massey, we know what happened to all but one of the central characters in this story.

"My Aunt Irene, along with her mom and sister, put young Ted on the train to California in late 1913 or early 1914,” Jan recalls. “They looked for him for years… writing letters into the 1960s looking for him. I think that image of putting a 5- or 6-year-old on a train alone must have haunted her all of her life. We always looked for Ted Steger but I have a feeling that we should have looked for him under the name of the woman who took him in when his mom died in 1918.”

Dorothy Steger died during the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918. For an unknown reason, Ted never seemed to be a part of Dorothy’s family after she remarried in California. He wandered, pretty much on his own, for four or five years. Another lady’s son befriended Ted and the McCormack family now believes they were looking all those years for the wrong name.

“That woman's name was Mona Chapman,” Jan said, “and he could have changed his last name to Chapman after her. Ted would have been only 10 when she took him in.”

The last word in this should come from Carl Sandburg, a man who won two Pulitzer Prizes and, according to the fall 1985 issue of Texas Library Journal, a professor that read The Letters of Harry Peyton Steger and recommended them to his college students because of Steger's unique gift with descriptive phrases.

Sandburg told an audience there would be no need to introduce him to Harry Peyton Steger once he got to heaven.

"I have read his letters," Sandburg explained. "I'll know him as soon as he talks."