In 1907, fortune was finally beginning to smile on one of the boys from the UT registrar's office. John Lomax was the first to strike a vein.

From childhood, Lomax had collected the lyrics of old cowboy ballads. As a freshman at UT in 1895, Lomax showed this collection to his English professor and was promptly ridiculed for his efforts. With many educated Texans of the era focusing on academia at the expense of Lone Star State's rapidly disappearing heritage, call it a textbook case of being too close to the forest to see the trees.

Fate intervened in 1907 when Lomax attended Harvard University as a graduate student where renowned scholars Barrett Wendell and George Lyman Kittredge recognized the need to preserve the fading legacy of the American West. So, while Steger was struggling through his first bitter New York winter, Lomax was about 190 miles to the northeast in Boston being encouraged to document his notes on the fading frontier. The eventual book, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, was published in 1910 and merited an introduction by none other than President Theodore Roosevelt.

While Lomax's first-year English professor at UT had rebuked this collection of lyrics so harshly that the humiliated freshman burned his collection, once the book was published Carl Sandburg observed that "The Buffalo Skinners" had a Homeric quality.

But, like Bedichek and Steger, Lomax would find it necessary to invent and reinvent himself time and time again. Lomax took a job teaching English at Texas A&M in 1903 and then was hired to fill an administrative position at UT in 1910 where he continued his research and lectured. However, Lomax was fired in 1917 as the result of a dispute between Texas Governor James Ferguson and UT president Dr. R.E. Vinson. In an interesting turn of events, Ferguson was impeached and Lomax was offered his job back. Instead, Lomax went into banking.

Along came the Depression.

Lomax found himself unemployed when the Dallas bank he worked for failed in 1931, but he suffered a much bigger loss that year when his wife Bess died. The couple had four children and now Lomax was raising the two that were still in school, including a 10-year-old daughter. He was 65, grieving over the death of his wife and out of a job.

But John Avery Lomax's finest work was still ahead of him.

In 1933, Macmillan Publishing decided to fund a project Lomax had invested most of his life researching, an anthology of American ballads and folk songs. His first stop was at the Library of Congress. But, instead of finding realms of written and recorded material, Lomax discovered that no one had the time or expertise to document the historic ballads, blues and folk songs being played by musicians from Appalachia to prisons throughout the South.

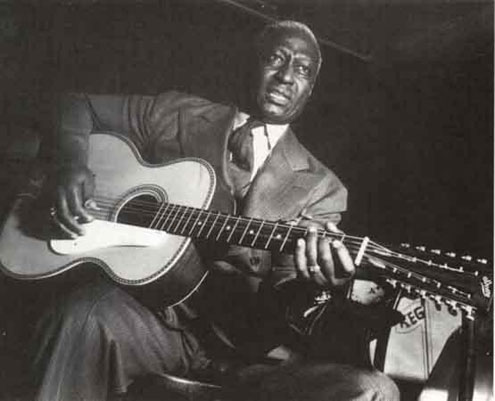

John Avery Lomax spent the next decade recording traditional music with the best equipment he could load into his car. His most famous session occurred inside the walls of Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola where Lomax discovered a talented, although troubled, 12-string guitarist that answered to "Lead Belly." That was the summer of 1933.

For the next 18 months, John Avery Lomax and his son, Alan Lomax, traveled the South recording musicians, but none were more intriguing than Huddy Ledbetter, better known then and now as Lead Belly. When Lead Belly got out of prison in 1934, he accompanied Lomax as a driver and also performed at lectures, but by the end of March 1935 it was clear the two men would not be able to work together. Lomax was afraid that Lead Belly would just drink up all the money he had coming to him, so Lomax began giving the money to Lead Belly's wife in installments. A lawsuit ensued, Lomax was required to pay Lead Belly a lump sum and the two men never worked together again.

John Avery Lomax died in 1947 of a stroke, leaving behind a body of work and a legacy that seems to grow more valuable with each passing year.

Lead Belly was on his first European tour in 1949 when he was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's disease. And Lead Belly's last concert? Well, he sang gospel songs with his wife, Martha. It was a tribute to John Avery Lomax at the University of Texas.

Previous Steger articles:

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_86954.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_86956.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_86957.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_86955.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_86965.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87117.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87118.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87121.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87207.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87123.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87213.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87214.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_69808.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87235.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87310.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87311.shtml

http://www.ntxe-news.com/artman/publish/article_87313.shtml