Increasing sustainability and lowering supplemental feed cost

Successful ranchers do not look for a “Silver Bullet,” but consistently concentrate on doing the basics very well. Times are changing, markets are changing, and common practices once used in the past need evaluation in order to determine their economic feasibility today. A common expense too many cattle produces is supplemental feed cost. The purpose of this article is to explain a few steps that may be taken to increase the sustainability of your operation, lower feed cost, and increase the profitability of your operation.

Learn how your plants grow

Plant leaves function like “Solar Panels.” These “Solar Panels,” or green leaves provide the factories of photosynthesis which produce 95% of the plants energy. Plant roots are responsible for the uptake of water and minerals which provide leaves with the products necessary for photosynthesis. Therefore, plant leaf area and root mass management becomes necessary for adequate biomass production.

Three different categories of grass species occur which include bunchgrasses (Kleingrass, & most natives,) indeterminate grasses (KR bluestem & Bahiagrass,) and sodgrasses (ie, Bremudagrass) which exhibit different growth forms based on their growth points. Bunchgrasses typically grow from a single base, have few growth points, and these growth points are usually above ground within reach of a grazing animal. Indeterminate grasses grow from multiple bases, have multiple growth points, but these growth points are usually out of reach from the grazing animal. Finally, sodgrasses grow on the ground surface with many growth points which like indeterminate species are typically out of reach of the grazing animal.

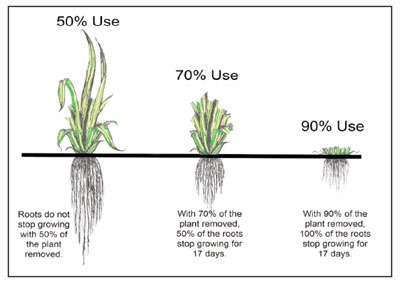

When you look at bunchgrasses, the mass and height of the leaves above ground represents the mass and depth of the roots below ground. When grazed, plants must not loose too much leaf area in order to maintain production. Studies have shown that most bunchgrasses can tolerate up to 50% leaf removal with little root loss. However when exceeding 50% leaf removal the aboveground mass will represent the belowground root mass. This means that the plant is not able to uptake as much water and nutrients, and does not have enough leaf area to provide adequate photosynthesis to quickly replace plant biomass.

If an extreme amount of leaf area is removed, the plant will exhibit very slow regrowth potential or possible death under drought conditions. For these reasons, we recommend the “Take Half, Leave Half” method when grazing bunchgrasses.

Unlike bunchgrasses, indeterminate grasses and sodgrasses have multiple growth points which are typically out of reach from the grazing animal, so grazing management of these species is different. Leaf area must remain intact for proper production, but instead of “Take Half, Leave Half” grazing, we recommend grazing to a certain grazing height. On bremudagrass, a 4 inch stubble height or 1,200 pounds of residual dry matter plant indicates the need for rotation to maintain productivity without delaying regrowth. Indeterminate grasses species have different stubble height requirements, but a good guide is 4 to 6 inches.

Stages of growth also occur within the growing season on all forages. The stages include vegetative growth, reproductive growth, and dormancy. Vegetative growth consists of leaf and stem growth. Plants have mostly leaf material and a maximum leaf to stem ratio during vegetative growth. This high amount of leaf material produces rapid growth with available moisture. The plant also stores food reserves during this stage. This stage of growth also produces the highest quality nutrition for the grazing animal. At the end of this phase, growth rate slows and the plant switches to a reproductive growth cycle.

Reproductive growth consists of leaf elongation, stem, and seed head growth. During this period, leaf production slows and plants expend energy from plant reserves to grow stems and seed heads. Additionally, leaf to stem ratio becomes much lower during this phase. This stage of growth provides lower quality nutrition for the grazing animal than vegetative growth. With proper rotational grazing, plants can be defoliated throughout the growing season to maintain vegetative growth, and better nutrition. However, the grazing methods mentioned above should be maintained in order to maintain production.

Dormancy is the final stage of growth and takes place in the winter for warm season perennial grasses. At this stage, nutrition is at lowest levels. The bases of these plants will provide area for plants to regrow the following spring, so a proper stubble height should be maintained because this is the start of your forage crop for next season.

Balance animal numbers with forage supply

The amount of forage you grow will determine the number of livestock your operation can support. We often refer to this as “Stocking Rate” or the number of animals supported on an area for an amount of time. Setting a proper stocking rate is the single most important factor of a successful grazing operation. No livestock grazing system will function properly if over stocked. For most cow-calf producers we determine year long stocking rates over the whole ranch in terms of acres per cow. Every operation consists of different resources, so each operation needs an objective look at soils, fertility, pasture composition, infrastructure, and grazeable acres in order to determine a proper stocking rate.

When stocking rates are very low, we expect excellent animal performance because the animal has access to enough forage to meet her demands. However very low stocking rates offer low financial returns, because not as much beef is produced per acre. With high stocking rates, animal performance suffers because access to forage becomes limited and a lower weight calf crop becomes evident. With higher stocking rates, supplemental feed costs through hay or other feeds are greatly increased to meet animal demands. This in turn lowers the profitability of the operation. With an optimal stocking rate, we can expect good animal performance with high return per acre. Also little to no supplemental hay is added to operation which in turn adds to increased profits.

In order to determine a proper stocking rate, you must assess your pastures and the condition of your animals together. A pasture exclosure as indicated above may function as a monitoring to assess forage consumed compared to actual year long production. This picture indicates high grazing pressure because less than 50% of consumed vegetaion exists compared to the refrence plot . As a “rule of thumb” we recommend that at least 4 inches of stubble is left for bremudagrass, and ½ of the height of bunch grasses.

Manage Body Condition Score (BCS)

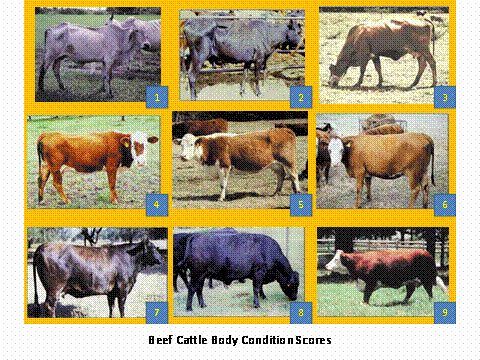

A body condition score consists of the measure of fatness and body composition of a cow. A score of 1-9 is assigned for beef cattle with 1 representing deathly thin and 9 representing drastically overweight. For a 1,000 pound beef cow, 70 pounds of body weight marks the difference between each BCS point. For beef cattle, we like to have a cow within the 5 to 6 BCS range. This will ensure reduced calving difficulty and proper lactation for offspring.

A lactating cow will lose some body condition throughout the season by the time a cow weans her calf. Often times BCS can drop to 4 or lower. Cows often lose a half pound a day while lactating, but if she starts at a mid 5 at parturition then she will end up a 4 at the end of weaning. However with proper stocking, condition can quickly rebound because adequate forage is available to meet the lower demands of a pregnant non-lactating cow.

Additionally you can feed 2 pounds of high protein feedstuff a day to quickly gain condition. For more information about Body Condition Scoring, contact your local NRCS, or Agrilife Extension Office.

Match animal demand to forage production

Another method of lowering supplemental feeding cost consists of establishing a breeding season that matches the time when animal demands are the highest with time of year of highest forage quality.

Pregnant cows can maintain condition with minimal protein supplementation during the winter months, and lactating cows will maintain more condition in the spring while lactating.

Utilize stockpiled forage

With proper stocking, carryover of forage at the end of the growing season will take place. Many producers will cut hay during the growing season and feed this back to their livestock in the winter. A common argument is that quality hay will yield better animal performance, and this is certainly true, but at what cost? With higher fuel and fertilizer costs today, many producers spend $40 to $50 to feed a roll of hay.

Instead, consider grazing “standing hay,” or stockpiled forage. With a controlled spring calving cow herd, you can supplement with cottonseed cubes or other feedstuffs with minimal cost to maintain a proper body condition score for your livestock. Remember that at this time, nutritional requirements for pregnant cows are not as high as a lactating cow. You can also extend the grazing period by interseeding cool season annual forages such as ryegrass or clover which provide even higher nutritional quality than warm season grasses.

Increase plant diversity

A cow has different nutritional requirements thought the year, and warm season grasses do not provide high quality nutrition year round. We discussed matching livestock demand to the growing season, but not every species exhibits similar growth and nutrition through the same growing season.

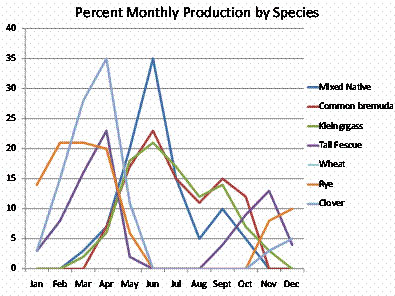

Data on available growth curves of particular forages may help you determine if species diversification is needed on your operation. These growth curves measure the percent production of a particular species by month. With multiple species in a growth curve the goal is to cover as much of the year as possible with some form of forage growth.

A single species such as Bremudagrass will produce forage from March thru November, but cool season forages can add some diversity and fill the forage gap during bermudagrass dormancy. Additionally, native grasses or Kleingrass will extend grazing longer into the dormancy period because these plants typically cure better than Bermuda.

Cool season and warm season species have a period when they typically all reach their maximum production level, but certain species still produce different amounts through the year. Additionally, not every year is the same and different growing conditions may favor different species from one year to the next.

Finally, consider native forage mixtures adapted to your area. Native grasses require little to no fertilization and some offer higher palatability and higher production potentials than many introduced grasses.

Plan for drought

Inevitably a drought will occur, so plan for it. One strategy is to use a stocking rate of 80% based on a normal year of forage production. If you have a year of above normal production you may choose to retain ownership of your calves longer, or incorporate stocker cattle. In dry years, you will not have to destock as quickly because an already reduced cow herd will allow more carryover of forages from last season. This approach offers more flexibility to your grazing operation.

By July 1, 65 percent of the warm season forage is normally produced. Assess forage production at this time or when forage production slows down due to lack of rainfall. If forage production falls below normal, then slow down rotations between pastures. This will allow pastures more time to recover between grazing periods. If forage in the original pasture has not recovered to meet your production needs, start implementing one or all of these strategies based on drought severity.

1. Start culling cows systematically.

2. Sell larger older calves first, and then sell younger lighter calves if needed.

3. Start supplementing hay or other cost effective feedstuff in a sacrifice paddock.

Make systematic culling decisions. Consider culling animals in this order:

1. Dry, open cows not raising offspring

2. Cows palpated open (not pregnant)

3. Animals with structural or production defects

4. Young replacement females (heifers.)

5. Cows palpated with short-term pregnancies (short-bred)

6. Older animals with offspring at side, but with worn teeth

7. Older animals with offspring at side

8. Thin, quality females, with offspring at side

9. Good condition, mid-aged females (4- to 8-year-old cows.)

Putting it all together

If we keep doing what we’ve always done, we’ll keep getting what we’ve always got. I hope this article will give you some options to consider on your operation. Remember that sustainability can reduce supplemental feed cost and possibly increase your economic success. You do not need to drastically change your operation today, but instead start off slow. You will make mistakes, but learn to recognize and correct them. If you have any questions, please contact your local NRCS office or Blackland Prairie Grazing Lands Conservation Initiative.