|

Columnists

Missouri guerrillas break up (or who was Fletch Taylor)

By Ronnie Atnip

Oct 20, 2011

In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and established the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. The Act was condemned by abolitionists because it allowing for the territories to decide whether to permit or prohibit slavery. This ignited a war inside Kansas between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions for control of the territory. This internal war became known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

Jayhawkers from Kansas began to invade Missouri, burn farms, take all personal property and in many cases, shoot or hang the pro-Southern farmers. The pre-civil war government turned a blind eye while the military actually condoned these incursions. Border Ruffians from Missouri began to invade Kansas for retribution.

Some personal property taken in Missouri was sold in Kansas yard sales, live stock was sold to the military, and anything of much value was warehoused, mostly in Lawrence, Kansas and sold in the Colorado gold fields via wagon train over the Santa Fe Trail. Freebooters, whom owed no allegiance to either party, joined the Jayhawkers and sold captured slaves in New Orleans (i.e. “sold down the river”) and shipped them out of New York Harbor to the Caribbean Islands.

When the Civil War erupted, martial law was declared because of the state of unrest. The elected government of Missouri fled to Marshall, Texas where it remained and functioned, although ignored, throughout the war.

Most of the Border Ruffians joined the Confederate Army leaving only independent bushwhackers to protect the people whom had Southern sympathies. The Red Legs and Jayhawkers were taken into the Union army, which gave them legitimacy. Then the Confederate Army mustered out those Missourians who wanted to come home and join the Bushwhackers and new recruits to form Partisan Rangers. These Rangers fought as guerrilla units in unconventional warfare. They did intelligence, sabotage, raids and ambushes, with most of thr operations being behind enemy lines. They had the element of surprise and mobility which allowed them to harass a larger and less mobile army or strike a target and withdraw immediately. These Rangers were outlawed and could be shot or hanged if caught.

George T. Maddox said it best about the regular army when leaving General Price to become a Partisan Ranger: “That kind of warfare did not suit me. I wanted to get out where I could have it more lively. Where I could fight if I wanted to or run if I so desired. I wanted to be my own general. I wanted personal encounters so that my own handiwork might become unmistakably manifest.”

Guerrilla forces tied down as much as one-third of the Union Army to occupational duties at different stages of the war. The Federal government attempted to mitigate the effects of guerrilla warfare with political policies that became so severe that they actually had the opposite effect.

William Clarke Quantrill took charge of a fifteen-man posse formed to pursue Jayhawkers. Charles Fletcher Taylor was one of these men. This group, originally formed to defend their homes, would grow to become the most notorious guerrilla organization in Missouri.

This posse evolved from Confederate soldiers and bushwhackers to Partisan Rangers known as Quantrill’s Raiders or Quantrill’s Guerrillas and was probably the finest light cavalry of the American Civil War. They made many successful raids, but the one most remembered is Lawrence, Kansas, considered payback by the Rangers.

At Lawrence, reconnaissance was very important. Red Legs, Jayhawkers and Union patrols were everywhere. Quantrill sent in his best spy team. Fletch Taylor posed as a wealthy land speculator, stayed at the Free State Hotel, and bought the best whiskey and cigars for everyone around. He was escorted across Lawrence in every direction, several times by land agents and land owners. He gained a wealth of information. The rest of the team was made up of the three Johns. John Noland, John Henry Wilson and John Lobb, all three black Missouri Partisan Rangers. Noland was supplied with a large amount of bribery money. He gained a lot of information which was all independently confirmed by Wilson and Lobb.

The guerrillas, having been outlawed, fought back with the same terms afforded them. It was total war. The raid on Lawrence, Kansas was very brutal. Over a four-hour period the town was looted and a quarter of the buildings burned. Between 185 and 200 male inhabitants were killed. After the sacking, the guerrillas did little fighting for the remainder of 1863.

Quantrill headed south for the winter and crossed the Red River at Colbert’s Ferry, north of Sherman, Texas. His camp was fifteen miles north of that city on Big Mineral Creek.

Quantrill reported to General Henry E. McCulloch. McCulloch was head of the North Texas Sub District, and was stationed in Bonham, Texas. McCulloch reminded the guerrilla chieftain that the general was in charge of this area and Quantrill reminded McCulloch that he himself had an independent command and was not under the general militarily. They did not hit it off.

McCulloch was constantly receiving requests for help from all over the area regarding crimes and terror committed by deserters, draft dodgers and union men. McCulloch, being undermanned, offered little help. North Texas was full of Missouri people who had been burnt out by Jayhawkers. The three Hill brothers, living in McKinney and members of Quantrill’s command, called on their chief for help. Quantrill sent a company of his best men to a swamp, known as Finch Park, where the bandits hid out. Forty-two men were caught, marched to the town square and all forty-two were hanged from a tree on the southeast corner of the square by the public well. McKinney became known as a “good place to live.” Quantrill did, however, have to go back and hang Collin County Sheriff James Reed and Deputy J. M. McReynolds.

McCulloch was enraged. He sent troops to Quantrill’s camp to disarm and dismount the guerrillas. Not wanting to be in that condition, Quantrill divided his troops and put one half in front of his camp down the road a ways and the other half in ambush positions joining the camp. When McCulloch’s soldiers approached, the forward guerillas fired over their heads and fell back to the camp. The soldiers did not take the bait and went back to Bonham. The officer in charge reported that “Quantrill is not a man to fool with.”

Quantrill was the law. McCulloch was pressured by his superiors to ask Quantrill to do police duties while in North Texas. Neither was happy about the arrangement, but Quantrill did such a good job that every outlaw in the area claimed to be in his command. This would keep them safe due to the soldiers being too afraid to shoot them.

General McColloch conferred with General Sterling Price and General Edmund Kirby Smith and it was decided that Quantrill could have no more than eighty privates and four officers. Quantrill selected George Todd as captain, “Bloody” Bill Anderson as first lieutenant, Fletch Taylor as second lieutenant, and Jim Little as third lieutenant. Captains Dave Poole, Cole Younger, and John Jarrette formed an independent cavalry and reported to E. Kirby Smith in Shreveport, Louisiana. Captain William Gregg and others joined General Joe Shelby. The Bonham, Texas recruits that went to Shelby were probably in this group.

Wise King, step son of Colonel Alexander, robbed and murdered one Mr. Froman about mile north of Sherman. Four guerrillas, including Fletch Taylor, retaliated by killing and robbing Colonel Alexander.

Then another murder shook the neighborhood. Major George N. Butts, owner of the plantation Glen Eden, was missing for several days and when found, it was discovered that he had been shot multiple times. Fletch Taylor and a few other guerrillas had been staying at Glen Eden as guests. When Sophia, the Major’s wife saw Fletch Taylor wearing her husband's watch, she accused Fletch of the crime.

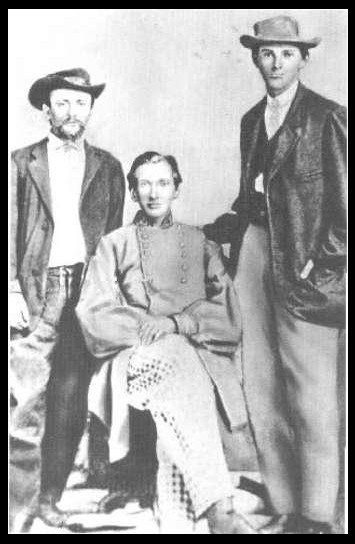

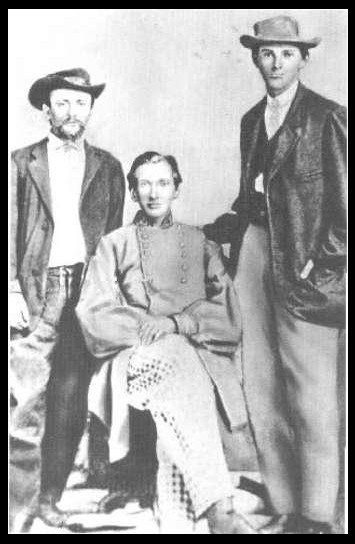

Photograph of Fletcher Taylor, Frank James and Jesse James, given to Charles Kemper of Independence, Missouri by Cole Younger who said it was made at Bonham, Texas in 1864. (OH, NO! Fletch has a watch chain visible. Is this evidence?)

Quantrill arrested Taylor, sent word to General McCulloch at Bonham, and requested permission to court-martial his prisoner. Fletch escaped and joined “Bloody Bill” who had moved to Sherman due to a falling out with Quantrill. Anderson, with Taylor, gathered their men and rode to McCulloch’s headquarters in Bonham. Taylor confessed to the murder of George Butts and added that Quantrill had ordered the killing and many other crimes. Mculloch sent word to Quantrill that Taylor was under arrest in Bonham and that he, Quantrill, was ordered to come to Bonham with his whole command and any witnesses for the court martial.

Quantrill, not trusting General McCulloch, took most of his command to Bonham, but left Captain George Todd and his men to guard the Big Mineral camp. Upon arriving in Bonham, Quantrill went to McCulloch’s office on the second floor of the Fannin County Courthouse where the General informed him of the confession and placed the guerrilla and all his men under arrest. It being dinner time (lunch), General McCulloch invited Quantrill across the street to the City Hotel to eat. Quantrill refused the offer and told McCulloch that he “found it strange that the General would take the word of admitted criminals over his and that he didn’t care if he never tasted another mouthful on this earth.”

General McCulloch went to dinner and left Quantrill unarmed with two privates of Martin’s Texas regiment standing guard. Quantrill crossed the room to get a drink at the water barrel and grabbed his six shooters off the table and unarmed his guards. Outside the courthouse he summoned his men and dispatched one who was mounted on a race mare to his camp above Sherman with orders for Todd and his men to bring all of the ammunition they could carry. They were to set up an ambush on the east side of Caney Creek crossing on the Bonham to Sherman road.

Quantrill left the Bonham square going south on Main Street and at Powder Creek headed east at a walk. After reaching Bois ‘D Arc Creek bottom, he headed north, still at a walk. He made a several mile ride north of Bonham and then circled south, to the Sherman and Bonham road. Bloody Bill, Fletch Tayor and men followed, out of shooting range with Colonel Martin and his men behind them.

Quantrill and the men with him, rode through the ambush site quickly, but did not draw Colonel Martin in. Anderson and Taylor were between the two forces and they stopped on the prairie. Todd invited Anderson to come in and Anderson invited Todd to come out. The two guerrilla factions started skirmishing and many shots were fired. The fight soon slid north through the timber and then across the creek. Colonel Martin refused to be drawn in, but did take some long range shots. Todd joined Quantrill and together they headed to Colbert’s Ferry. Martin followed to the Red River and then headed back to Bonham.

After crossing the river, they splintered into guerrilla groups under captains, never again to unify as a force. Captains George Todd, Bill Anderson, and Archie Clements were all killed in separate actions in Missouri. Quantrill was killed in action in Kentucky. Fletch Taylor survived the war fighting in Missouri with his own command which included later to become the infamous Jesse James.

By 1871, Fletch had became independently wealthy by developing and operating lead mines in Missouri. He was elected to the Missouri State Legislature and served on the Missouri General Assembly. Taylor later moved to Nebraska where he owned and operated stage lines. At the age of fifty he moved to California and expanded his stage line business. Charles Fletcher Taylor died at the age of seventy of natural causes.

Ronnie Atnip is a hobby historian, twenty year member of the Fannin County Historical Commission and a member of the newly formed Captain Bob Lee Camp, Sons of Confederate Veterans.