Unique in many ways, the Mary Slough Museum in downtown Enloe, seven miles northeast of Cooper is likely to become a favorite Texas historical showcase for visitors who spend an hour with Richard Duncan, director of research, genealogist, and chief volunteer.

“Most of the people who find their way to the museum are not from around here. They come from Hawaii, Illinois, and all across the country to discover the Delta County roots of their ancestors who once resided here,” Duncan explains.

Few leave disappointed after mentioning an ancestral Delta County family name to Duncan. If he does not respond immediately with information from his encyclopedic memory, he pulls from the shelves one of the hundred or so loose leaf notebooks filled with maps, photographs, genealogical information, and lists of related families. Some researchers will spend a six-hour day finding answers they could locate nowhere else about their heritage.

Enloe, once a bustling town in the center of cotton fields, had thriving businesses and small industries. With a population of ninety today, Enloe is a serene community of well kept homes and loyal citizens. The Enloe State Bank was one of its most notable institutions until a branch was opened in Cooper, the county seat, in 2010. Then the Enloe flagship bank closed, and only the Cooper branch now remains open.

One of the standout buildings near Enloe in the old Darwin community is owned by one of the Carrington brothers Jace and his wife, Susan, who live in Dallas but often retreat to Enloe, where Jace grew up. The Texas flag painted on the side of their Enloe home is a landmark in the area.

The museum opened three years ago with great encouragement and financial support from Edwin Slough. The museum name honors Edwin Slough’s late mother, who taught in several area schools. The building housing the collections had served a variety of functions previously, most recently as an automotive garage. With no paid employees, the museum depends upon volunteers and monetary gifts for its operation.

One of the ideas setting the collection apart from other museums is the vision of Richard Duncan, a native of adjoining Lamar County, and of his wife, Nancy Young, an Enloe native still working at the Cooper branch of Enloe State Bank and serving as director and curator of the museum. Their home is a mile north of the North Sulphur River in Lamar County, not far from Enloe. Since his retirement after thirty-five years as a crane operator for a Paris boiler company, he has been a fulltime volunteer in sharing what he has discovered about Delta County families. In partnership with his wife and other associates, he has undertaken the Delta County Homestead Project, which also includes public buildings and institutions.

His approach is to begin with the name of a homestead or institution, many with unknown locations. Through maps, surveys, and local history, he locates the site of the property and carefully examines the land, even though the original structures may no longer be standing. When he discovers the homestead or institution site, Duncan begins research by taking a new, all-important direction. He looks for tangible relics that can relate descendants to the lifestyle of their ancestors. Once Duncan acquired a rolling pin donated by the granddaughter of the man who whittled it on the front porch of a long-vanished home. He put it on display in the museum with photographs and maps of the homestead to allow descendants to unleash their imaginations while scrutinizing the rolling pin. The relic never fails to trigger connecting sensations.

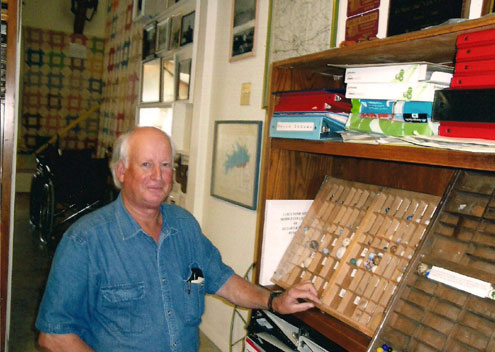

One of Duncan’s favorite displays is a type case filled with numbered marbles corresponding to a numbered list of homesteads at which the game pieces were found. Although he has no evidence that the marble belonged to a resident there, the object is enough to give the viewer a link to the site.

Throughout the museum other relics on display with written details of the homestead engage the visitor. Another display for the Unitia School has a piece of a school desk, marbles, and nails to make the extinct institution live again. Duncan is unaware of any other collection that uses this concrete approach. Systematic surveys of homesteads are underway in all parts of Delta County except the far western edge.

“We want to start in the Klondike area soon,” he says.

“Once a homestead is located, we move back in time from the target family, listing every known occupant on the site. Then we move forward into later families and expand our investigation to neighboring land,” Duncan explained.

Delta County was formed in 1870 from Lamar County to the north and Hopkins County to the south to ease travel to a county seat when the North Sulphur obstructed the route to Paris or the South Sulphur obstructed the route to Tarrant and could not be crossed when the river flooded. The area that is northeast of Cooper was known as Yates Prairie before Delta County was organized, and it was the location of some of the earliest homes and of two of the first Methodist churches organized in July and December 1854. The museum has acquired copies of the Lamar and Hopkins county records related to present-day Delta County before 1870 to give researchers complete information without requiring trips to Paris and Sulphur Springs.

Unexpected celebrity encounters engage the attention of browsers. For example, Hetty Green was one of the wealthiest women in America when her Texas Central Railroad was built through Enloe. Her sobriquet of “the witch of Wall Street” reminded everyone of how she was regarded. Nevertheless, evidence gives testimony to some benevolence in Enloe. In Enloe she donated land for a Baptist church and other public sites. In a more egocentric gesture, she laid out the streets of Enloe, naming north-south streets for males in the Green family and east-west streets for females in the family. Hetty’s son, Edward Howland Green, left his mark on Delta County when his railroad passed through, and he chose the name of Katy for a community on the western edge. A resident of Terrell, Green chose the name to honor a young lady from Dallas he was dating. When Katy applied for a post office, the name duplicated another Texas station at the time. With Green’s lapsed interest in the Katy namesake, he did not object to local residents selecting Klondike, chosen because the gold rush in that northern region was in the news.

Another celebrity family taking the spotlight at the Enloe museum is the Hockaday clan, owners of land in northwestern Delta County. A Hockaday daughter, Ela, founder of the prestigious Dallas school for young ladies, had lived in Delta County before moving to Dallas and founding the institution. In recent years the grandson of Richard and Nancy Duncan was a pre-schooler at Hockaday, which accepted male students until the first grade, and they provided the school with information about the Hockaday homestead, as well as a display of oyster shells and gravel to provide tangible relics of the North Sulphur River area.

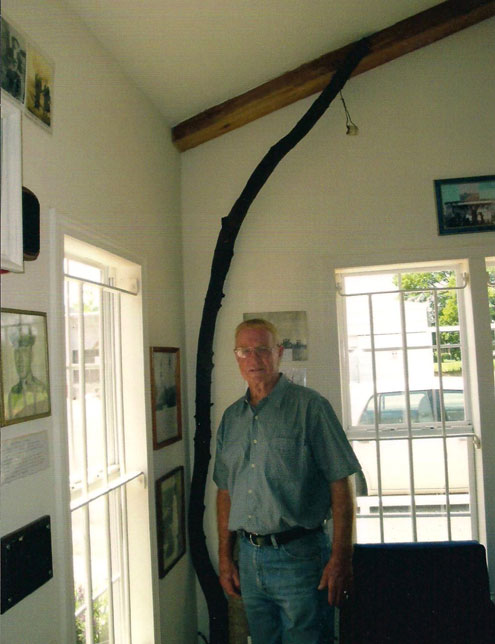

Two visitors to the Enloe museum on Wednesday, June 15, 2011, were Jim Ainsworth, Delta County native from Klondike and award-winning novelist; and Jerry Lytle, a bois d’arc craftsman who lives in Hopkins County just east of the South Sulphur River. Both men are civic leaders in Commerce, designated by the state legislature as the Bois d’Arc Capital of Texas. Their mission was to find exhibits of bois d’arc in the museum that would quality Delta County with a minimum of three “bois d’arc destinations” for admission to the Bois d’Arc Kingdom. These Northeast Texas counties are the only spot on planet earth where the tree has grown as a native since the last ice age 120,000 years ago.

A map will soon be issued with numbers in each county that is a member of the Kingdom, identifying bois d’arc attractions. A descriptive paragraph will give details about what is to be found at each location. The purpose of the organization of the Kingdom is to instill pride in the bois d’arc tree among Northeast Texas residents and to attract tourists to discover the role bois d’arc plays presently and historically. The other two qualifying initial bois d’arc destinations in Delta County are the North Sulphur River, which attracted the first humans to the area because of growths of valuable bois d’arc wood for Native American bows and arrows, and objects made of bois d’arc in the Delta County Historical Museum in Cooper.

The two visitors from Commerce found more than enough displays to include the Enloe museum as an official bois d’arc destination. For example, impressive exhibits show two sections of bois d’arc paling fences from Delta County homesteads, one of them revealed in a photograph of the site; an unusually long stretch of straight bois d’arc serving as a telegraph/telephone pole with an insulator still attached; an impressive length of bois d’arc used as the main drive shaft of a gin in nearby Mount Joy; a sharp pointed fence pole from Fort Shelton, built in 1836-1837, thought to have prevented bears from entering the stockade since four feet of the pole would have been in the ground, not leaving enough height to prevent Indians from scaling it; and a bois d’arc pestle used in Oklahoma to pound corn and other food stuff placed in a mortar, donated by John David Griffitts of Lamar County.

Ainsworth and Lytle left the Enloe museum as satisfied about their bois d’arc discoveries as any genealogist who had just exposed a pivotal fact about an evasive ancestor. Duncan posts regular museum hours in a front window of the building: 10 a.m.-3 p.m. on Friday and Saturday; 1 p.m.-3 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. Other times may be arranged by appointment by calling Richard Duncan at his home at 903-784-8114 or at the museum at 903-395-0519. The museum plays a central role in Enloe homecoming each September. One visit to hear Duncan’s stories about the gumbo pit in Enloe or the three robberies of the Enloe bank will bring visitors back for many more scoops on Delta County history.